Transcript

music

“Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs

oliver

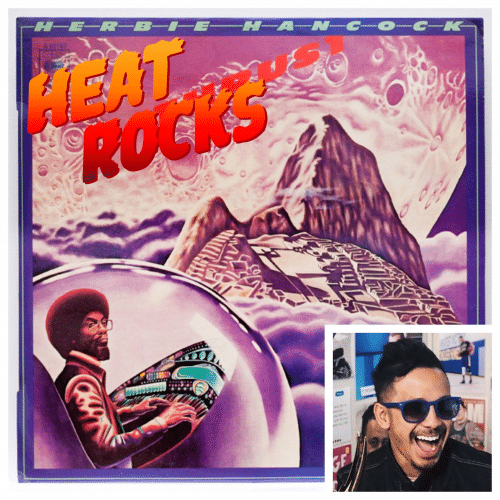

Hello, I’m Oliver Wang, flying solo today. Shout out to co-host Morgan Rhodes who will be back soon. You are, by the way, listening to Heat Rocks.

jason concepcion

Ooh, it’s hot.

oliver

[Laughs.] Every episode, we invite a guest to join us to talk about a heat rock, that is, an album that sizzles. And today, we’re firing up the rockets to fly back 35 years to talk about Herbie Hancock’s 1974 album, Thrust.

music

“Palm Grease” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock. Funky, groovy, electronic, jazzy instrumental. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out.

oliver

Herbie Hancock came into 1974 riding a bolt of lightning. His Head Hunters album from the previous fall ruled the charts well into ’74 and its heavy dose of funk elements—colored in swatches of cutting edge synthesizers—didn’t just make a splash in the jazz world, but it rocked the pop charts too as Hancock’s first platinum seller. By that summer, he went back to the same San Francisco studio, with most of the same players, and assembled another four-track LP in a similar jazz-funk-fusion vein. This one, he named Thrust, and whether the title was inspired by Hancock’s on-going exploration of afro-futurist themes or just an apt metaphor for the velocity of his early 70s career, Thrust yielded Herbie another bestselling jazz album and further cemented him as one of the era’s most consistent commercial and creative forces.

music

[“Palm Grease” fades back in. A groovy, jazzy saxophone has joined the fray. After a few moments, it fades out again.]

oliver

Thrust was the album pick of our guest today, Jason Concepcion. A few years ago, in the halcyon, pre-2016 days of Twitter, before it descended into the morass of outrage and despair it is today, I started following an oddly named account named “netw3rk”—that’s spelled with a 3 in place of the second e—written by someone who I thought was a social media comic genius—and I swear to god, that’s meant to be a compliment—who seemed to have equal love for Game of Thrones, corgis, and for some inexplicable reason, the New York Knickerbockers. Jason eventually came out west from his native New York City where he is now part of the mighty Ringer hive mind, who has done everything from re-cap the entirety of Game of Thrones in podcast form, he is currently one of the senior “Succession” and “Mindhunter” analysts and just this year, won a Sports Emmy for his NBA Desktop which should be returning by the time this podcast airs. He also, as he just reminded me, has a background in music, and originally studied to be a film composer, so this seems very apropos as a conversation.

jason

Let’s go.

oliver

Jason, you are already one fourth your way to an EGOT. Welcome to Heat Rocks.

jason

That’s right. The thing about the EGOT though is you gotta get the weird ones out of the way first, so the Grammy is obviously the hardest. [Oliver laughs and agrees several times.] I don’t know if I’m gonna get there. You know, James Corden I think can get it. He’s the guy—he’s the next guy who I think can get it, because he got the Tony out of the way, I think the Oscar one is gonna be the tough one, but he’s got the rest of his career.

oliver

He could go for maybe an Oscar in some technical field that we just—

jason

That’s the thing—

oliver

—he could be a screenwriter, maybe?

jason

—it’s like, he could do a Kobe thing where it’s like he back—you know, best animated feature—

oliver

There you go.

jason

—you know, as a producer and kind of get in in the back door. [Both laugh.]

oliver

When it came to figuring out what you were gonna pick for this, I realized, even though I’m so familiar with you for your basketball work, but I didn’t have a great sense of what your musical tastes would be, so it’s not like I had heavy expectations on what you might choose. But I have to say that Herbie Hancock’s Thrust probably would not have made the top 100 albums I might have guessed—

jason

Sure.

oliver

—that you were gonna pick. So why this particular album? What makes it a heat rock for you?

jason

Well, a lot of my musical tastes depend on stuff I can write to, write currently. So I’m listening to a lot of different interpretations of the Goldberg Variations by Bach right now for writing, I listen to a lot of like mid-60s Miles Davis for writing, and Thrust is this perfect venn diagram of no words, so I can just kind of zone out when I listen to it, and stuff that I have a deep emotional attachment to, because of like a journey I went on. So this kind of like a—when I went to college, I went to Berklee College of Music, got very into jazz because you kind of have to, so I was listening to a lot of like, Bill Evans, Jim Hall, John Coltrane, which I love, but is also so ethereal and analytical and it’s like, “get the chord chart out, what are they doing, what inversions are they using?” and it was so academic that when I discovered funk, it was just like, a relief. [Oliver agrees several times while Jason speaks.] So I got very into like, P-Funk and Parliament and stuff like that, and then just was like, okay, give me everything that came out at that time. I’m gonna go on this funk journey. Let me find tower of power, let me find Cymande, and then I found Head Hunters, which was the 1973 Herbie Hancock album that you noted, which is kind of like “the famous one”. It’s got—

oliver

I mean, it’s a bestseller. Huge album.

jason

Huge, I mean, think about a time when jazz albums were in the top ten of the Billboards charts. It just doesn’t happen anymore. The 70s were super weird. You know, there was like, porno movies in the top ten of the Box Office charts also, so it was a time when kind of like the space between high and low culture had completely evaporated, and that’s part of what I really appreciated about Herbie’s discography during this time. So, Head Hunters comes in and it’s “the pop” version of this great backbeats, very—it’s all about the beat and about texture and then the thing that I love about Thrust is it brought that kind of—the complexity of jazz and married it, in my view, perfectly to the beat.

music

“Spank-A-Lee” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock. Upbeat, fast jazz with a saxophone main line and a heavy synth backing. Music plays for several seconds.

jason

And another difference was they brought in Mike Clark on drums— [Music fades out.] —to team with Paul Jackson, two Oakland Funk guys, and Oakland funk is really characterized by a, you know, like the importance of just playing in that pocket.

oliver

Right, super tight.

jason

Being in that super, super, super, super tight drums and bass, like handcuffed to each other. Now when you take the kind of… swing… drum style of jazz with the kind of tight pocket bass of funk, what is gonna happen—and to me, what happens—is that in particular the second track off this album, actual proof which, to me, pre-stages some of the drum and bass movement of the mid-90s or the 2000s. Um, it’s just a perfect record for me in terms of beat, in terms of melodic exploration and textural exploration, and it’s just an album that you can leave on. I think it, like—fusion is, in a lot of ways, like a bad word.

oliver

Sure. I mean, especially amongst a certain kind of cadre of jazz purists, it definitely is a bad word.

jason

And that’s kind of what I like about it. [Oliver laughs.] This is before—this is like—this is a real kind of like genre-bending exploration in a sincere way before you got the kind of like overwrought Weather Report-y Mahavishnu Orchestra like, kind of stuff that would eventually become smooth jazz. Like, this was when real exploration in jazz was vital. In a lot of ways it was like the last gasp before smooth jazz kind of like, absolutely erased what was kind of cool about these explorations.

music

“Butterfly” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock plays. Slower jazz with a sax and an almost electronic, synth-y beat.

oliver

So, I gotta spin back on a couple of these things. Let’s start with this, is you are saying that a song like— [Music fades out.] —”Actual Proof” off this album is effectively proto-drum and bass.

jason

Yeah. Like, all you gotta do is take the BPM and bump it up like, by 15-20, and that’s drum and bass— [“Actual Proof” begins fading in.] —in the middle of this track when it really gets simmering.

music

“Actual Proof” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock plays. Fast jazz with rapid piano and a synth and drums/cymbals backing. Piano increases in tempo rapidly, then comes to a crescendo with a crash of the cymbals. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out as Oliver speaks.

oliver

Some intrepid listener should certainly go out there and compare what you just heard with 90s drum and bass and see if you find the similarities there. I’m also wondering though, if we could actually go back into your personal listening history. So, if you didn’t really discover funk, or at least this era of funk, until you were already well into college, what was a young teenage Jason rocking? What were you listening to as a kid?

crosstalk

Jason: I was listening to like, classic rock, and then like— Oliver: Like we talking Zeppelin and Stones? Okay. Jason: —the rock n’ roll of the day, like Zeppelin, uh, I was listening to like, the freaking Eagles. Oliver: Okay.

jason

I was listening to like, uh, Van Halen—which like, here’s the thing about Eddie Van Halen, actual genius. Truly a person who wedded technical virtuosity with a real kind of like curiosity about the way electronics work. Like, forget what you know about like, David Lee Roth and Sammy Hagar, etcetera. Look at some of the instrumental tracks that he created, like “Cathedral” off of, um, Diver Down. Terrible album. [Oliver laughs.] “Cathedral” is a melodically layered piece using volume pot swells and delay to create essentially what is like a cello piece? [Oliver makes a noise of agreement.]

music

“Cathedral” off the album Diver Down by Van Halen plays. Bare electric guitar played in such a way that it sounds almost cello-like. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out.

jason

The guy was like, legit. Legit as a musician at that time, so I was like very into that. I was very into anybody who was doing different things with sounds, a guitar, or any instrument could make. And I was listening to like, jam bam music also. Like, I was like, how can you be—so this is like, late 90s, right, when grunge was really the thing—how can you be a musician in that milieu and that, what I found was like, jam bam stuff and this kind of weird psychedelic music. So I was like, “How can I be a musician on the guitar during this time?” That was like, the thing I was going through at that time.

oliver

Well, also it strikes me that that description of Eddie Van Halen as marrying technical virtuosity with an interest or curiosity about electronic and technical, sorry, technological innovation, you could really apply the very same thing to what Herbie Hancock was doing throughout this entire era, because—

jason

Yes, that’s the thing I like.

oliver

—he’s got like five synths on this album, right?

jason

Five synths like, very into the ARP at that time.

oliver

Yeah, ARP is heavy on this.

jason

ARP is heavy on this, and ARP is, you know, like state of the art synthesizer for the 70s and legitimately fills a room, like it looks like—you actually need a person to come in and switch like the cords in the middle of stuff. Sounds super cool and super retro but also was just like a state of the art machine at the time, and that was like, I really loved that kind of thing. You know, like Herbie got very into—really, at Miles’ urging—electric piano and Rhodes piano. You know, Miles was always like, he tried to make Keith Garrett do it too, and Keith Garrett like hated it. Herbie initially resisted it but then got very, very into it and explored it in that. And I really appreciate people who want to explore the technical as well as the kind of more wrote, traditional melodic and rhythmical sides of music making.

oliver

And if listeners are curious as to how to distinguish the ARP from, let’s say the Rhodes, to me not every use of the ARP has this particular sound; but whenever I think of the sound of the ARP synthesizer, it’s always much more of this high pitched almost kind of whine.

music

“Spank-A-Lee” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock plays. Drums with a high-pitched synth. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out.

oliver

[Jason agrees several times while Oliver speaks.] You really have to just disentangle because I feel like there’s quite a few things perhaps overdubbed there, because you can hear some of the more mellow Rhodes piano in the background—I’m gonna talk more about the Rhodes in a moment—but again, Herbie was really open to playing with a lot of different sounds, a lot of different keyboards. I don’t think this is outrageous to say at all, that he, to me, reminds me of being the jazz equivalent to what Stevie Wonder was doing in the world of R&B and soul, because, you know, Stevie I think more than perhaps any other artist of his ilk, he brought the clavinet into the game, and the clavinet is on this album as well.

jason

Yes. That was a big—clavinet, to create that kind of like funky, almost like, [makes “wacka-chica” musical sound] you know, like guitar sound was a huge technical and textural innovation in this kind of music.

music

“Palm Grease” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock plays. Electronic, synth-y jazz with a clavinet that creates a sound similar to an electric guitar. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out.

oliver

So since we’ve been talking a little bit about Herbie—and maybe just dropping a little bit deeper into his kind of career arc, especially in this moment—I think what’s notable about Thrust and about Head Hunters is that it comes really in this, if you look at the grand 20 year span, it comes about a decade after he begins recording as primarily an acoustic piano player, he’s recording for Blue Note Records, his sound is very, very much hard bop of that time.

music

“Watermelon Man” off the album Takin’ Off by Herbie Hancock plays. Mid-tempo jazz with sax, light drums, and piano. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out.

oliver

And then ten years after Thrust, you get to your mo—you get to his moment with Future Shock in the song “Rockit”; which I think a lot of people probably—if they were of my generation at least—if you were introduced to Herbie Hancock, it was really through Future Shock and through “Rockit” because of his embrace of proto-hip-hop.

music

“Rockit” off the album Future Shock by Herbie Hancock plays. Funky, jazzy electronic music with a beat reminiscent of hip-hop. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out.

oliver

This album with Thrust is, this is—you can draw this line, maybe it’s not perfectly linear, but you can draw this line from “Watermelon” in 62 to “Rockit” in 82 or 83, and Thrust kind of shows you where he’s going along this grand arc.

jason

Yeah, Herbie had been embracing kind of this melding of R&B for lack of a better word styles for quite a long time, and I think that the thing about Thrust on this arc is it’s part of a general trend towards how virtuosic can we get that I think was happening in music, um, popular music on the whole at that time. You know, like, the Beatles had created this thing of like, how virtuosic can we get in a studio? And the next thing you know you have Queen, who’s sort of multi-layering full operatic styles, and you have ELO that are taking it to the next level of that. That creates a backlash, which is punk. Next thing you know, R&B kind of takes a hard ship and becomes like, proto-hip-hop and then hip-hop proper. And I think, for Thrust, you really—it’s a snapshot of a time when that trend line of how much more technical, how much more virtuosic can we be was still kind of trending up, and it was really interesting to me, before all of that stuff kind of got swept away. I think when you play that clip of some of his ARP riffs, the thing that I realize is like, those are really kind of horn stabs. Like if you were gonna—if you were writing out the chart of that, and were gonna arrange that for an orchestra, those were like, [imitates ‘bap, bap’ horn sounds] those are like horn lines, and the thing that became, you know, the thing that became soft jazz was like, the synthesizer people who were using synthesizers eventually were like, “Oh, what if we actually did horn sounds? What if we actually made it sound like horns?” And then that—people were like, “Oh that’s cheesy, that’s terrible.” That kind of like, Weather Report Joe Zawinul kind of like actual horn shit, um, became the thing that people absolutely rejected and was not cool, but to me was cool at this time, because it was like horn sounds but not horns.

oliver

So I have so many questions that stem out of this. So you’re arguing that in a way if it’s a backlash or a paring down, so in the world of rock all this kind of virtuosic work ends up creating the inverse of that which is super raw, and that’s punk music, right? Hip-hop you could argue that—by the time especially you get into the Run DMC era, and with the use of drum machines—this is a reaction to the influence of disco and kind of disco’s excesses, if you will. And in jazz, you’re saying that there is a comparable backlash, except it doesn’t produce something that’s very cool.

jason

Yes, exactly. You know, I think the 70s are interesting because it’s like, there was a lot of philosophical soul searching for what is like, the actual true essence of the genre. So in rock n’roll, it was like how do we, you know, if I’m a kid starting out and I listen to ELO or Queen, “I’ll never be able to do that, so like, what can I do?” And then you have Television and fucking Talking Heads and the Ramones and whatever. And I think it’s a similar thing. It was kind of different in jazz, which was, “Oh, I’ll never reach the level of virtuosity that Herbie Hancock has, I’ll never be a legend like Miles Davis, but if I just put funky drums behind a thing, and kind of have like, kind of jazz-y changes, now I’m like the Yellow Jackets, and like at least we can tour Japan and stuff and play at wineries.” [Oliver agrees several times while Jason speaks.] And that’s a career. It’s two different kinds of rejection, but one is kind of like settling for a thing, and the other is a search for the true essence of it. I think, you know, in a lot of ways jazz has been kind of, like, placed in amber ideologically. You know, there’s this idea of, um, as soon as people went electric, it’s like almost the Bob Dylan thing. As soon as people went electric, like jazz went away. It really is like upright bass piano and like horns.

oliver

Kind of the Wynton Marsalis school of jazz traditionalism.

jason

Which holds power and skill, you know, jazz at like its center is still the Wynton Marsalis philosophy of what jazz is. And to get back to Herbie, what I love about this record is, here’s a vitality in experimentation before the kind of Wynton Marsalian argument had really taken hold and frozen an entire genre essentially in people’s minds.

music

“Palm Grease” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out.

oliver

You were—we were talking earlier about the notion of whether fusion is used as a bad word, and I think it obviously depends on who you’re speaking to, but I think within what you’re describing here, the particular politics, the ideological traditions within jazz, fusion I think more often than not is seen as being very much negative, and it’s just something I was thinking of in terms of how I came to discover this particular sound and era, and a lot of it was coming directly out of me growing up as a DJ and as a record collector—and really, I think record collector sounds even too polished. I was crate digging in the 90s like a lot of people who were really into hip-hop and were looking for samples, and so as a result of that, you would end up almost— [Jason agrees several times.] —there’s no way that you could have avoided having a shit ton of milk crates full of fusion records, because this is what people were using, so whether or not—and this is all from the same era in the 1970s, so I’m thinking of everything that includes stuff by, we’ve been talking about like, the Weather Report for example.

music

“Young and Fine” off the album Mr. Gone by Weather Report. Smooth, groovy jazz. Music plays for several seconds, plays quietly under Oliver’s dialogue, then crossfades into “Fire Eater” as he speaks.

oliver

It certainly includes a lot of what people describe as rare groove, which is very much that late 60s, early 70s Blue Note and Prestige style.

music

“Fire Eater” off the album “Fire Eater” by Rusty Bryant. Upbeat, groovy jazz with a bit of funk. Music plays for several seconds, plays quietly under Oliver’s dialogue, then crossfades into “Hydra” as he speaks.

oliver

Or if you’re in your early 20s and you’re dead broke, you just pile up a lot of dollar bin CTI and Kudu records.

music

“Hydra” off the album Feels So Good by Grover Washington Jr. plays. Higher-pitched, lighter, grooving jazz. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out as Oliver speaks.

oliver

But as time goes by the bragging rights of owning shit that Diamond D sampled for like two bars just didn’t really necessarily seem like enough of a reason to keep this, unless you were really into the sound itself. And I think—for me, at least—I don’t mind admitting that it didn’t really age well for me. And I remember back in 2006, which is the summer that I moved from the Bay Area back down here to Los Angeles, I had a stoop sale of just purging records that I didn’t want to have to bother packing and shipping, and I think probably about eighty percent of those were fusion jazz LPs that I just felt like, “I’m never gonna be listening to like, say, this Lonnie Smith LP again. I just don’t need to keep it around.” And so, it’s not that I reject fusion as an idea, because I want to feel like I can embrace a lot of stuff, but there is something about the sound that as time goes by—and I feel like maybe this was part of the debate at the time, I wasn’t really there to hear it—is that there is a lot about fusion that people just weren’t into then and still now. Do you have a sense of what it is that people are reacting to so negatively?

jason

[Oliver agrees several times while Jason speaks.] Yeah, I think that there is a—when the groove overpowers the kind of improvisational elements, I think that is when you start tipping the balance into something that is just kind of like background music, is more kind of like a smooth jazz idea; which I think is not, to me, is not a thing that’s happening in this record, where Herbie is, you know, being so forceful and trying out different sounds and layering different ideas and there’s like odd time shit happening and like this real business in the rhythm section but also a tightness that is really interesting. I think that when you, um, when it started getting pared down into just kind of like, just groove with kind of like a hint of a melodic idea and some kind of like organ or rhode stabs, just because, I think that’s the thing that people rejected. It just was, it just—and I kind of agree with this—it was just kind of easy, you know, there was no experimentation there, it was just like, let’s—here’s a groove, here’s a backbeat, here’s a cool bassline, or kind of a cool semi-interesting bassline with just like the hint of a melody on top of it, and that’s a song, and that’s a record, and we’ll probably make some money off of this.

oliver

It’s interesting, because I actually think, I approach it personally from the other direction, which is that a lot of the fusion that I couldn’t hang with over time is stuff that I think is just best described as being very noodling, which is ill-defined, but you kind of know it when you hear it, which it sounds like a bunch of people like, just endlessly playing riffs or whatever over basslines.

jason

I think that that is—the overwroughtness, it is such a balance, because that’s true too. There’s the overnoodling and the over, kind of complexity of the thing, which is like, you know, Return To Forever and stuff, which is these like middle riffs that just kind of like go on forever and there’s like the third movement and now the fourth movement— [Oliver laughs multiple times.] —and now the fucking organ solo and now we’re gonna go to the—it seems like crazy to be like, “Actual Proof” is great, it is very tight at nine minutes. But for that era, it was very tight. You look at some of these Return To Forever albums and it’s like, you got a twenty minute fucking song on there with like five movements. Um, there was at least some kind of a ruthlessness that was still evident for me in Thrust. This is, and again, this is the end of the line for me, this is the moment, 1974 Thrust, where, this is as far as you can take it, and now you need to figure out something different.

music

“Actual Proof” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock plays.

oliver

We will be back with more of our conversation with Jason Concepcion about Herbie Hancock’s Thrust after we hear from some of our fellow MaxFun sibling podcasts. Keep it locked. [Music plays for several more seconds, then fades out.]

promo

Music: Quiet rock. Aimee Mann: Hello, this is Aimee Mann. Ted Leo: And I'm Ted Leo. Aimee: And we have a podcast called The Art of Process. Ted: We've been lucky enough over the past year to talk to some of our friends and acquaintances from across the creative spectrum to find out how they actually work. Speaker 1: And so I have to write material that makes sense and makes people laugh. I also have to think about what I'm saying to people. Speaker 2: If I kick your ass, I'll make you famous. Speaker 3: The fight to get LGBTQ representation in the show. Ted & Aimee: Mm-hm. Speaker 4: We weirdly don't know as many musicians as you would expect. Speaker 5: I really just became a political speech writer by accident. Speaker 6: I'm realizing that I have accidentally, uhhh, pulled my pants down. [Someone starts to laugh.] Ted: Listen and subscribe at MaximumFun.org or wherever you get your podcasts. Speaker 7: It's like if the guinea pig was complicit in helping the scientist. [Music ends.]

promo

[Background music.] Renee: Well, Alexis, we got big news. Alexis: Uh-oh. Renee: Season one? Done. Alexis: It's over. Renee: Season two? Coming at you hot! Three years after— [Both laugh.] Alexis: Three and a half. Three and a half. Renee: —our season one. Alexis: Technically almost four years. Renee: Alright. Alright. And now it—listen! Alexis: Hm? Renee: Here at Can I Pet Your Dog?, the— Alexis: Yes. Renee: —smash hit podcast, our seasons run for three and a half years. [Alexis laughs.] And then in season two, we come at you with new, hot cohosts. Named you. Alexis: Hi, I'm Alexis. [Both laugh.] Renee: [Laughing] We also have, uh, future of dog tech! Alexis: Yeah! Renee: Dog news! Alexis: Dog news? Renee: Celebrity guests. Alexis: Oh, big shots! Renee: Will not let them talk about their resume. Alexis: Nope! Only their dogs! Renee: Yeahhh, only the dogs! I mean, if ever you were gonna get into Can I Pet Your Dog?— Alexis: Now is the time. Renee: Get in here! Every Tuesday at MaximumFun.org.

music

“Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs

oliver

We are back on Heat Rocks, talking about Herbie Hancock’s 1974 album Thrust with our guest, Jason Concepcion. Jason, before we dip back in the album, I feel like it would be remiss if we didn’t get into at least a little with basketball give that—

jason

Oh, let’s do it.

oliver

—we have a senior NBA mind here—

jason

Let’s go.

oliver

—and one of the questions I had for you is that I think one of the major narratives that we hear about the NBA right now is that it’s turned into a 365 league, especially with all the intrigue that you see in the off season, and 2019 might be the capstone of that. I certainly don’t disagree with the assertion insofar as I spend way too much time, especially in the off season, reading NBA Reddit for example.

jason

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

oliver

But I’m wondering, and I’m just thinking of this as, you know, my day job is as a sociologist, and so if there is a shift in the cultural phenomenon, I’m always wondering like, what has influenced that? And so with this and the idea of the NBA expanding its cultural influence and its social import, is it a combination, or which one of these things is legit, is it because the media and especially the role of social media has changed to keep stories, you know, a constant stream? Does it have to do with changes in the game itself, that people are more interested in it? Or does it have to do with a particular conglomeration of personalities that we have that makes it appealing? And I’m wondering, what is your explanation for how has the NBA made this shit into a 365 league?

jason

That’s a great question. I think at the root of it, if you’re gonna trace this kind of trend back to its beginning, I think you have to talk about the NBA’s kind of initial decision, which was born of necessity, as the fifth most important sport—like, when it started in the 40s and 50s, the NBA was not on the map at all, and the way they decided they were going to hype up their sport was that they were going to promote individual players. There’s a famous picture of the Minnesota Lakers—Minneapolis Lakers playing the Knicks at Madison Square Garden, it says Mikan vs. Knicks. Right, George Mikan was the original superstar of the league. So it’s the idea of lets promote the players. There’s only ten players on the court, and they give them time, and that kind of like personality, that became the kind of personality-driven thing that reached to culmination with like, Magic vs. Brewer, that really saved the league.

oliver

Or Dr. J before that.

jason

Dr. J before that, and a kind of like perfect marrying of style and substance. So that created the kind of entry point for what social media, this kind of like, rise of social media, then perfectly amplified, which is a personality driven league where you can, your entry point can be talking about analyzing stats and actual game information, or being like, “I like the way this player does this move.” Kind of like this aesthetic way of engaging with league. So that’s one is the kind of personality driven thing that happened that was with the roots of the game. And then I think the fact that the NBA has been, since the rise of the internet, really hands off with its content. I think that might be changing a little bit now, but you know, the NFL, the MLB, you can’t retweet or repurpose some game clip with your own music and make a meme out of it, they’ll take it down. The NBA has been like, “Do whatever. Do what you want.” And so that is kind of like, hyper—you know, that’s I think scary in a certain sense, because you’re giving away agency to a bunch of different, to basically the internet, and who knows what their intentions are. But what that’s done is created this entire ecosystem of internet discourse around the league, and it’s really made it interesting and vital and almost like a meta way to follow a sport. [Jason agrees several times while Oliver speaks.]

oliver

Right. And I hope this is not too fast of a comparison, but what you just said instantly made me think of this idea, take it, run with it however you want, that’s so hip-hop. And it’s not coincidental that most of the people that I came up with who were all hip-hop fans, their favorite sport, their favorite American sport at least, is basketball. I mean, far more so than football, or hockey, or baseball, and it’s not— I’m not saying anything new in terms of the relationship between hip-hop and basketball, especially from the personalities, but the idea that, from a content point of view, the ways in which NBA content circulates among us has that kind of, “Just go with it, do whatever you want with it.”

jason

Yeah, I think that that is—that’s the lens through which to view this, and why NBA discourse is kind of like different than any other sport really, is that open-handedness that the league has thus far taken with their content. They’ve allowed people to use it and repurpose it in ways that are really interesting.

oliver

Can you imagine any timeline in which the NBA overtakes the NFL as the most popular American sport?

jason

Hmm. No. Not—could it happen? Yes. I think that there are obviously structural things that the NFL is dealing with that are hampering both the quality of the game and the way people view it. You know, I think that the, you know, I was talking about this with some friends last night, you know, like twelve years ago there’d be a massive tackle, some huge hit, and you’d be like, “Yeah! Get ‘em!” And now that happens—

oliver

Now it’s all CTE.

jason

Yeah, now it happens and you’re like, “Oh, I hope that guy’s okay.” I think that that is a structural issue that the league is gonna have to deal with, but football is massively popular. Massively, massively, massively popular. I think it will be generations before that is even a thing that we would think about. You know, will football wane in popularity? Sure. I think that as we learn more about CTE and its role in the game, I think that will happen, but I think it will be a long, long time before the NBA overtakes football, at least in this country, you know.

oliver

Well, hard shift back to talking to—about Thrust here, but coming back to Herbie Hancock and his album. If you had to pick—and this is only a four track album so, you know, there’s a one in four shot here—what would you pick out of that quartet, what would be your fire track?

jason

My fire track is “Actual Proof” because it is the, um, it’s to me the one time, really the pinnacle of marrying jazz and pocket funk in a way that is interesting, not over-noodly, has the kind of like core characteristics of both. Mike Clark is doing this little swing thing on the hi-hat, but also like, Paul Jackson is somehow holding down what is like a really pocket bassline, and it works. It would never, ever work again. [Both laugh.] I don’t think it ever worked again. But to me, that is, it’s a magical track. There’s also like a weird, odd time—I think it’s like a measure of five in there. I don’t know how all that stuff works, but it does manage to work. Um, and that to me is the track.

music

“Actual Proof” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock plays.

oliver

The music historian in me just loves learning about discographic backgrounds, and this song, I think is also perhaps the most interesting of the four songs on here, partly because it begins life as the theme song to the Blaxploitation film from ‘73 that Hancock was hired to do the music for, which was The Spook Who Sat By The Door, which—

jason

Controversial film.

oliver

Yeah, ‘cause it’s all about basically like, the CIA’s infiltration of Black radical movement. It actually in a lot of ways feels very contemporary now.

jason

Yeah.

oliver

Um, and there is actually also, and we were talking earlier about the instrumentation that Herbie Hancock is using, so we were talking about the bank of A-R-P, of ARP synthesizers, but also there’s a lot of Fender Rhodes electric piano here, and that’s the instrument that Jason was mentioning that Miles Davis introduced Herbie to, and a lot of jazz players were getting into the sound of the Fender Rhodes, which is very warm, people describe it as being bell-like. Once you hear it, you’ll know what it sounds like. It’s kind of like a Wurlitzer, but somehow even more suffused with this kind of warmth. And in ‘73, CBS records teamed up with Herbie Hancock to produce a flexi disc which was basically a flexible, plastic phonograph record that I want to say was shipped in issues of—probably Downbeat, maybe some other jazz magazines. And it was a demonstration album—or I should say a demonstration single—of Herbie Hancock talking about what makes the Fender Rhodes electric piano so useful and important and all the things it can do. And he actually talks in this flexi disc about the theme song to The Spook Who Sat By The Door. He talks about how this song is a song is a song that he’s basically re-recording or repurposing for his upcoming album, which means Thrust in this case, and we can take a listen to a quick clip of him talking about this and then playing us the song that eventually would be called “Actual Proof.”

clip

[Flexi disc recording of Herbie Hancock plays.] Herbie Hancock: Earlier this year, I wrote the soundtrack to a film called The Spook Who Sat By The Door, and we re-recorded it for our latest album, and we had a lot of fun doing it. Here’s a short segment of the theme song from The Spook Who Sat By The Door. [“Rhodes Piano Demo”, a demo version of “Actual Proof”, plays.]

oliver

So the original version of “Actual Proof” back when it was The Spook Who Sat By The Door featured drummer Harvey Mason who had played on Head Hunters, but Harvey couldn’t join the group on tour— [Music fades out.] —or in the recording studio, which is how Mike Clark came into the game, because him and bassist Paul Jackson were old friends, and so they ended up re-recording the song, this time with Mike Clark on drums, and Mike in the liner notes to one of the reissues of this album talks about how the title “Actual Proof” was influenced by Buddhist concept, and Mike before he went into the studio, went into an empty room, chanted for twenty minutes—

jason

70s, man.

oliver

—you know, exactly, right? [Jason laughs.] Came back in, and apparently I think they recorded this in a single take.

jason

That’s fucking crazy.

oliver

Right. Yeah, he’s talking about kind of virtuosic performance and whatnot, so. Yeah, I just love the kind of different layers you can explore through just one song and all the intersecting stories that connect from it.

music

“Actual Proof” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock plays. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out.

oliver

My favorite song off of here I think is gonna be “Butterfly”, and I think partly that’s because in some ways it’s perhaps kind of the more conventional songs. It’s a ballad, the groove is a little bit sparser, it reminds me more of something that I might have heard of Head Hunters, whereas songs like “Palm Grease”, which we haven’t talked much about, or “Spank-A-Lee” which we heard a bit from before, were for me perhaps just a little too frenetic or maybe also too fonky, which is “funk” spelled with the “o”. [Jason laughs and agrees.] Which I think is, that’s the dark side of Oakland funk is when it becomes Oakland fonk.

jason

Yeah, I agree with you.

oliver

Yeah. But “Butterfly” just has this beautiful, just, it just has this beautiful groove to it, and it also, the song yields my favorite moment off the album, which comes toward the end of the song, and there’s a bridge where suddenly everything gets stripped down, and you hear the main theme return.

music

“Butterfly” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock. Music plays for several seconds.

oliver

Parts of it remind me of something that maybe the Mizell Brothers might have produced for Blue Note in that same era, and this point in the song in particular, and I mean this in the best possible way— [Music fades out.] —but it’s sort of what I want to hear if I’m sipping a cocktail at 8 p.m., that has some place with low lighting but a really nice view, and that just seems to be—kind of capture that. Do you have a favorite moment off of this album?

jason

Oh, man. That’s a great question. It would be somewhere in the peak of Herbie’s solo in “Actual Proof”, when you can’t, and it’s kind of hard to figure out where you are in the track, and then Mike and Paul hit that [imitates the bassline and drums from the song] and then it just goes right back into the thing, so it would be like, towards the kind of like peak of Herbie’s solo, where you’re just like, where are you in this, and then they—

oliver

They anchor you back in.

jason

—catch you—they anchor you back in, where you’re just like, “How are you guys doing—I don’t understand how this is happening.” You know, going to music school, I would hear students, people who were beginning their musical journeys like, try and play this track, and it’s just like, man, you realize how hard it is to do what it is that they’re doing and not make it sound bad.

oliver

Right. By the way, I always imagined at music schools—and this is someone who hasn’t gone to one, so this is pure invention perhaps—but I always just think of them as being very stayed and very conservative and traditional, so I’m just wondering, an album like this, was this something that your music teachers would have encouraged or embraced?

jason

No. I mean, this was like—my experience of music school was, one it’s kind of unnecessary. Like, if you can play, you go for a semester, you get the experience of meeting all these other players, and then you realize, “Oh, I’m good. I’m gonna go leave and get a job. Like, I’m gonna be John Blackwell and I’m gonna play for Prince or whatever it is.” Or, you really dive into the knowledge that you can’t get otherwise, which is like the more producing and the technical aspects, which I was interested in but not super interested in. But for me the experience of music school was like, this kind of free exchange of ideas and a really cool, like meeting of the minds. The thing that I really appreciated about it was like, being able to be like, “Hey, it’s one in the morning on a Friday, let’s jam in a practice room and just like, work this stuff out.” That was really cool.

jason

You know, and learning about how to say stuff with music, I think that I’ve written about this, but the biggest lesson I learned was, it was like Freshman year, I got into—I had—through the audition process, I had scored high enough to be in a jazz lab, and we were playing some like blues in F, whatever, and I was taking my solos, and usually you would take two choruses and then signal out, and then the next person would come in. And I took my solo, signaled to come out, and the teacher was like, “No, you’re gonna keep going.” So I played another chorus, I was like, “I’m gonna come out.” “No, you’re gonna keep going.” And this went on for like, I don’t know, I probably took like, legitimately like a dozen choruses on this tune, and I realized through that process that like, everything that I knew how to say on my instrument was basically like, half a chorus of it. I needed to figure out how to say stuff on my instrument, so that I wasn’t just like, mindlessly re-creating riffs. And that was like, a painful lesson, but actually a really good one. Like, have something to say within, or else you’re just gonna sound like you’re noodling.

oliver

And you were playing guitar.

jason

Yeah.

oliver

So was there a point where the music teacher threw a guitar at you, like Whiplash-style.

jason

No, that never— [Oliver laughs.] It—that never happened! It never happened.

oliver

Is there a contemporary artist that you would want to hear take on any of the songs on here, and what would the song be and who would the artist be?

jason

Oh, man. I don’t… No, I don’t think it’s possible. You know, like, I got really into like, post-rock and math-rock for a little while. One of the albums that I put forward was a toe record. Toe was like this kind of, weird math-rock Japanese band.

music

“two moons” off the album For Long Tomorrow by toe plays. Up-tempo, gently cheerful instrumental music with drums and guitar. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out.

jason

It’d be cool to hear them—their take on music like this, but on the other hand, I think it’s really a moment in time that has passed. You know, like I don’t think anybody could try and recreate this.

oliver

Right, and maybe it’s partly because—and this is not to say that compositionally these are not great songs, but—it really marks a moment in time. I think we’ve been talking a lot about this throughout our episode, that what you can hear in it besides the musicianship, it’s also thinking about the trajectory of where jazz and pop music was going at this moment in the mid-70s, but it’s not, like, in and of itself such a great fucking tune that you necessarily need to hear it done in 2019 or 2020, whatever.

jason

Again, this is, to me, the pinnacle of this particular form of exploration and it’s kind of—that’s it. It’s reached the end of its evolution at this point. This is the highest it’s gonna get.

oliver

If you had to describe Thrust in three words, what would you choose?

jason

Funk—well, uh improvisational funk perfection.

oliver

[Sounding delighted.] Mmm! I like that!

music

“Palm Grease” off the album Thrust by Herbie Hancock plays.

oliver

For listeners who really liked Herbie Hancock’s Thrust, we have some recommendations for what you might want to check out next— [Music fades out.] —and for me, I went to one of my favorite jazz albums from 1974, so the same year that Thrust came out, which is Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson’s Winter In America, which is—I mean, we could have done a whole episode about that album. It is such a heat rock as well. Such a sublimely soulful and melancholy album that’s also very deeply social, spiritual, and personal, and political.

music

“Peace Go With You Brother” off the album Winter In America by Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson plays. Gentle, passionate R&B. You're my lawyer, you're my doctor Yeah, but somehow you forgot about me And now, now when I see you All I can say is: peace… [Music fades out as Oliver speaks]

oliver

Jason, how about you? Where would you tell people to go next after Thrust?

jason

Well, I would, you know, pick up Head Hunters, the album that really kind of preceded this and is a landmark album, I guess, of the form, and certainly a landmark jazz record. Um, highly sampled, and the simpler version of this record.

oliver

Right, I think a lot of people describe Thrust really as like a part two or part B to Head Hunters’ part A.

jason

Yeah.

music

“Chameleon” off the album Head Hunters by Herbie Hancock plays. Upbeat, groovy jazz-funk, similar to what we’ve heard off of Thrust. Music plays for several seconds, then fades out.

oliver

That will do it for this episode of Heat Rocks with our special guest, Jason Concepcion. What are you working on now?

jason

Oh, man. Binge Mode. We’re doing Binge Mode: Star Wars.

music

“Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs

jason

And so we’ve begun the recording process on that.

oliver

Explain Binge Mode real quick?

jason

So, Binge Mode is—Mallory Rubin, my co-host and I, diving deep into a particular subject, usually fantasy-based. So we started this with Game of Thrones, we did one episode per episode of Game of Thrones, analysis, kind of critical analysis and jokes, then we did a Harry Potter section, where we explored all the books and also the movies, and now we’re doing Star Wars in similar fashion. We’re exploring the movies, some of the extended universe stuff, and comics, um, character studies, etcetera.

oliver

Normally we would ask you for what your contact, where people can find you online, but I mentioned that in the intro, which is that you are on Twitter @netw3rk, and the second E you replace with a 3. I’ve always meant to ask, what does that symbolize? Where did that—where did your Twitter handle come from?

jason

That was my, um, my Xbox Live gamertag.

oliver

Boom. [Jason laughs.] Where else can people find your stuff online?

jason

Um, it’s—that’s it, check TheRinger.com and YouTube for NBA stuff coming back as soon as the NBA season comes back, and hopefully we win another Emmy. That’s all.

oliver

Yeah. Alright. Fingers crossed. Jason, thank you so much for coming through.

jason

Thank you.

oliver

You’ve been listening to Heat Rocks with me, Oliver Wang and Morgan Rhodes.

morgan

Our theme music is “Crown Ones” by Thes One of People Under The Stairs. Shoutout to Thes for the hookup.

oliver

Heat Rocks is produced by myself and Morgan, alongside Christian Dueñas, who also edits, engineers, and does the booking for our shows.

morgan

Our senior producer is Laura Swisher, and our executive producer is Jesse Thorn.

oliver

We are part of the Maximum Fun family, taping every week live in their studios in the West Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles, and I know I usually try to come up with a pun here, but Thrust is only four songs, I just couldn’t do anything with it, I’m so sorry. I’ve been long overdue in thanking our reviewers on iTunes. Just this past week we had jpodblue writing in to say that they enjoy the deep dives and that our podcast is “great for long commutes”. Glad we can keep you all company in your cars out there. We also had notadad write in to say we are “the best podcast out there. It’s that simple, y’all.” Indeed it is that simple. I’ll take that, we are the best podcast out there. If you had not had a chance to leave us a review on iTunes, please do, because it is a key way that new listeners can find their way to us.

oliver

One last thing, here’s a teaser for next week’s episode, which features myself and guest co-host Ernest Hardy, speaking with artist and author Tisa Bryant about The Emotions smash 1977 album, Rejoice.

tisa bryant

It’s probably the sweetest and most emotionally enriching album I can think of. It’s unfreighted. You know, there are so many other albums I could think of that had a kind of weight to my life or something happening, and this album isn’t marked for me by anything but joy and possibility and aspiration, because those voices, you know, as a kid, who wouldn’t want to sing one of those parts as well?

speaker 2

Comedy and culture.

speaker 3

Artist owned—

speaker 4

—Audience supported.

About the show

Hosted by Oliver Wang and Morgan Rhodes, every episode of Heat Rocks invites a special guest to talk about a heat rock – a hot album, a scorching record. These are in-depth conversations about the albums that shape our lives.

Our guests include musicians, writers, and scholars and though we don’t exclusively focus on any one genre, expect to hear about albums from the worlds of soul, hip-hop, funk, jazz, Latin, and more.

New episodes every Thursday on Apple Podcasts or whatever you get your podcasts.

Subscribe to our website updates for exclusive bonus content (including extra interview segments, mini-episodes, etc.)

Meanwhile, you can email us at heatrockspod@gmail.com or follow us on social media:

People

How to listen

Stream or download episodes directly from our website, or listen via your favorite podcatcher!