Episode notes

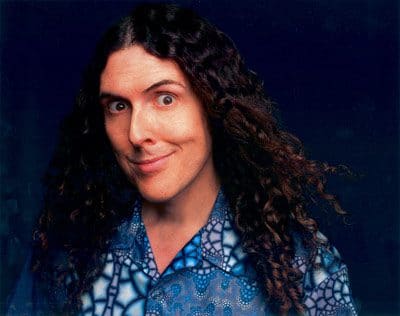

Weird Al Yankovic is the undisputed king of parody music and the all-time bestselling accordionist. His new children’s book is When I Grow Up. His new album is due this summer.

JESSE THORN: I’m tempted to say that my next guest needs no introduction, except that it occurs to me now that this is the radio and you can’t see him. He’s Weird Al Yankovic; probably the best song parodist of all time. He’s sold more than 12 million records, and now he has a brand new book for kids called When I Grow Up that was a New York Times best seller. His new record comes out in the summer, and it’s such an honor to have him on The Sound of Young America. Weird Al, welcome to the show.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I appreciate that, thank you.

Click here for a full transcript of this show.

JESSE THORN: I hope that ramp up was suitable.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: You impressed me; I’m excited to be here.

JESSE THORN: Okay, good. It’s got to be fun to be you, I got to tell you. Why don’t we start by talking a little bit about your childhood? I know that you went into school early and then skipped a grade early on in elementary school, so you ended up spending much of your childhood two years ahead of your age peers and two years younger than your grade peers.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: That’s a good way to put it.

JESSE THORN: No, it’s a terrible way to put it. It was totally baffling. People are driving their cars on the freeway right now trying to do arithmetic.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I know what you’re talking about, and that’s the main thing.

JESSE THORN: Okay. So you double skipped.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Yeah, so for example if you’re doing the math, I started high school when I was 12 years old and graduated when I was 16 – – actually, did I start when I was 11? I graduated when I was 16; I know that much for sure. I would say that that maybe made me a little bit less comfortable with my peers or maybe felt more out of sorts, but in all honesty I think even if we were the same age I would still have been the odd man out. I would have still been the nerdy kid that didn’t quite fit in anywhere, so it probably made very little difference that I was two years younger than most of my peers in school.

JESSE THORN: Do you really think that’s the case? I remember when I was in elementary school and there was talk of changing what grade I would go into, and my folks vetoed it based on the fact that they were worried that it would be weird, basically.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Yeah, I think that’s probably a conversation my folks had at some point. These were the same people who decided I should take accordion lessons, so I don’t think they worried too much about me fitting in.

JESSE THORN: So did you like playing accordion? I know that it was your parents’ idea; was it appealing to you?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I didn’t see anything wrong with it when I was seven years old; it seemed like an okay enough idea at the time. I was playing classical pieces and polkas, of course, and standard compositions; traditional songs. It seemed perfectly logical to me that I would take accordion lessons. It wasn’t really until I hit my early teenage years when I wanted to actually play with my other friends that played musical instruments that I realized I was being ostracized. For some crazy reason, they didn’t want an accordion playing in their band. That’s when I first realized that the accordion maybe is not the hippest instrument in contemporary America.

JESSE THORN: Did you reject it as a teenager at any point?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I stopped taking lessons after about three years, so around age 10 or so I decided I was just going to – – I don’t know if it was because I was tired of it or felt like I could learn better on my own but I just kind of set it aside for a few years, and then I picked it up again a little bit later just for fun to play along with the songs on the radio. I could play by ear pretty well. I remember I used to have Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road album completely memorized and I could play it on the accordion, and my friends thought that was hilarious. They for some reason thought there was humor in the juxtaposition of accordion music and rock music, which is something I’ve carried on in my oeuvre to this day.

JESSE THORN: When you were 15, 16 years old, did you want to make music that was funny, or did you want to make music that rocked and would make you a cool rock and roll guy?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I don’t think I ever had any aspirations to be cool. I thought that was sort of out of the question. I just wanted to amuse my friends. Again, I never really thought I’d ever make a living doing this; I’d probably have my rock star fantasies like every other kid that sings into their hairbrush in the bathroom mirror. It was always just for grins. I think that maybe I went through a stage that lasted about twenty minutes where I was trying to write a serious rock song or a serious pop song, and I wrote some execrable lyrics and I looked at them and said no, this isn’t going to work. My brain is too warped to take this seriously; I have to kind of follow my muse which is to do demented music.

JESSE THORN: You used the phrase demented music, which is the descriptor for the music that was played on the Dr. Demento radio show, which was a popular syndicated FM radio show that was sort of a clearinghouse for every type of novelty song and piece of funny music. When did you first hear that show?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I think when I was maybe about 12 years old a friend of mine turned me onto it, he said there’s a show on KMET Los Angeles, an FM station in LA, Sunday nights, four hours, he plays nothing but weird funny crazy music. I thought, that’s right up my alley, and I started listening and was immediately hooked. It went on a little bit past my bedtime so after lights were out I would have the alarm clock radio under the covers and I’d be listening to the funny five or the top ten. I listened to it religiously; it really was an important part of my life. After a while my friends were saying, why don’t you record your own stuff and send it into the show. Well, I could do that.

So I recorded myself singing along with my accordion just on a little tiny cassette tape recorder in my bedroom. Cassettes were like three for a dollar, even the stock was cheap. But I sent them to the Dr. Demento show, and to my utter amazement he played those songs on the radio. I just could not fathom this was happening; stuff that I just recorded in my bedroom was now being heard by the whole listenership of the Dr. Demento show.

JESSE THORN: I want to play a little bit of one of the first songs that you sent to Dr. Demento. This is a song called “Belvedere Cruisin’.”

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: You have that? Wow.

JESSE THORN: The internet, my friend.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Oh, yes. Everything’s on the internet, it’s amazing.

JESSE THORN: How old were you when you recorded this song and sent it in?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I was either 15 or 16.

JESSE THORN: Wow. Let’s hear a little bit of my guest Weird Al Yankovic and his very first song, Belvedere Cruisin’.

When you hear that song or think about that song, do you feel like you recognize a voice or a person that you later became as an artist?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Everything’s gone downhill since Belvedere Cruisin’. That was so raw, so punk. So feral and so intense. I don’t think I’ve ever matched that intensity.

JESSE THORN: But sincerely, that is really, I think the theme of that song, it’s a song about – –

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: It’s a love song about my parents’ car. I think every artist has one of those songs in their catalogue.

JESSE THORN: It’s also a song that has a classic Weird Al juxtaposition, which is essentially fronting like you’re cool in the way that popular music does, and that being sort of reality checked by something very banal.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: That, again, is a very nice way to put that. Yes. Let’s go with that.

JESSE THORN: Speaking of songs that have that theme, I want to play a little bit of your first big Dr. Demento hit, which is a song called Another One Rides the Bus.

Tell me a little bit about how you recorded this record.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Another One Rides the Bus was written very very quickly. It was actually over a weekend where I went on a camping trip with Dr. Demento and a couple of other friends, we’d actually become friends during my high school year because I would send him recordings and he’d play them and we developed a bit of a relationship. He invited me and I think our friend Beefalo Bill and Damascus and other people who had been friends of the Dr. Demento show to go on a little trip. Over that weekend I think I dashed off the lyrics in 20 minutes because the Queen song was a big hit on the radio. I thought maybe he’ll let me play his song on his show that Sunday night. I told him about it and he said yeah, we’ll have you debut it on the top ten.

So I had my accordion with me during the show, I got ready to play, and I said if anybody wants to make some funny noises while I’m playing feel free, Musical Mike you can make your hand flatulence sounds and everybody else just do whatever; I think we practiced it once out in the hallway. There was this guy who said I’m a drummer, I could bang on your accordion case, I said yeah, that’s great. So Dr. Demento introduced me, Alfred Yankovic and his magic accordion, or whatever it was, and he turned on the mics and we did Another One Rides the Bus.

I didn’t think anything other than it went pretty well, and then I went off to college because I was 19 years old at the time and was just on break from school. Went back to college and about a week later my roommate was telling me, there were some messages for you on the phone, there’s some radio station in New Zealand that wants a copy of Another One Rides the Bus. I was getting all these crazy messages from all around the world of people trying to figure out how to get the song. It was on the Dr. Demento show which was syndicated nationally, but the song really took on a life of its own, it was viral in the days before things went viral. People were desperate to get a copy of this thing. That was the beginning of it, it came out eventually several months after the fact, after the bloom was far off the rose, but didn’t quite get out in time to make any real splash.

JESSE THORN: So the question that I want to ask you about that whole scenario that you just described is what is it like to go on a camping trip with Dr. Demento and the stable of artists from the Dr. Demento show when you’re 19 years old and everyone else is, I’m sure, roughly the same age; maybe there’s some like 43 year old guys that record on their Ham radio. I’m trying to figure out what this scenario is like.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Dr. Demento was the oldest guy there; most of us that were answering phones and hanging out were probably college age and mid-20s. It was a fairly young group, actually. Dr. Demento did not wear his top hat when he was camping, that’s about the only time you’ll see him without his top hat. I don’t remember much about the weekend, I don’t even remember where, somewhere in southern California, we just went out to a cabin some place and went hiking.

JESSE THORN: I’m just imagining like, “Time to barbecue some WEINERS! WOO WOO WOO!” In the crazy Dr. Demento voice. He was a guest once on The Sound of Young America, and a very nice man.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Yes, he is.

JESSE THORN: What was the point that these dalliances in recording and performing became an earnest attempt at building a career that could pay your bills?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Probably not until after I graduated from college. I proceeded to try to take a shot at getting a bona fide record deal. It was a period of a couple years where I knocked on a lot of doors and sent a lot of tapes around, and the general response was, oh, this is really funny, you’re very clever, possibly even genius, but we’re not interested because this is novelty music. If you’re lucky maybe you’ll have another hit single or something, but we’re looking for people to have long careers and this is just not the genre that we want to be involved with.

JESSE THORN: What were you listening to in the 1980s when you were first building your career?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I’ve always been drawn – – well, of course there’s the Dr. Demento artists which inspired me in the first place, but in terms of contemporary artists I was really inspired by the whole new wave scene. I guess it’s more like late 70s, but the B-52s and Devo and Oingo Boingo, Talking Heads, things like that. That carried over into the 80s a bit, as well. Anything that was a little quirky and left of center I took a lot of inspiration from.

JESSE THORN: This was a time when the music landscape was really changing a lot, just as it had in the 1970s with the advent of FM album oriented rock radio was changing the 1980s into a world that was driven by new radio formats and also MTV that had video. What was the first real studio produced attempt that you made that really worked?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: The first album that we did was done on spec. It was produced by Rick Derringer. I should probably explain how that came about. I get permission to do the parodies, and one of the parodies that I was recording was a parody of Joan Jett’s hit I Love Rock and Roll.

JESSE THORN: Which, correct me if I’m wrong, was I Love Rocky Road?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: That’s correct sir. That was a cover version for her that was originally done by a group called The Arrows. One of the gentleman in The Arrows who also co-wrote the song was who happened to be Rick Derringer’s manager.

JESSE THORN: Was that your first genuine radio smash?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: There was a demo of that song that came out before the album. It was sort of like we were trying to get – – we recorded the first album on spec very quickly, very cheaply, and I would say poorly. It was a product of the time. We had the demo of the song which we leaked to Los Angeles radio, and it actually got a fair amount of airplay on a couple of the top-40 stations. We used that exposure to create the buzz that we hoped would get us a record deal. Again, we were still having a tough time from all the record companies, they all thought that this was novelty; this is not something we want to dirty our hands with. Finally a company called Scotti Brothers decided they would take a shot at it.

JESSE THORN: Your albums are often roughly half original compositions and half parody songs; usually with a polka medley thrown in. I want to play one of your earlier successful original compositions which is called Biggest Ball of Twine in Minnesota.

This is another one of your tunes, an original that is about that sense of suburban banality. I wonder how you felt about that in the early and mid-1980s when there was sort of this buzz of satire of that; like, attacks upon that that was left over from punk rock, in part, and also an ironic celebration of camp, which was, at the time, just kind of making it into the mainstream.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Right. You can read a lot into my body of work – – I think that irony plays a lot into it. And certainly there’s a theme running through my songs of celebrating banality. I’m sort of alternative music as it is, but everybody else was writing songs about love and loftier things, and I thought that to stand out I could be writing songs about lunch meat or twine balls or whatever the case may be, and just celebrating the minutia of everyday life.

JESSE THORN: I was thinking of Eat It. I’m 29, so that was a big thing in my childhood, Eat It. Both Beat It and Eat It. I worshipped Michael Jackson and I loved Eat It. I was thinking about how that is just simply about the simplest thing it could possibly be about.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Yes, I’m thankful that there was no YouTube in 1984 because otherwise there would have already been 10 million Eat It parodies before I ever got around to it.

JESSE THORN: It really takes this most basic human function and just explodes it into an absurd opera; the absurd opera that pop music is, often.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Right. I did a lot of songs about food, especially in the 80s. I’m not really sure why food, it just seemed like a really easy thing to write songs about. It might be left over from my days as a starving musician, I don’t know. It’s come in handy because I have written so many songs about food, I can totally write off any kind of food that I eat. My grocery bill is a tax write off, I need it for inspiration for my songs.

JESSE THORN: In the early 1990s there was a huge push against that pop excess that you had parodies so successfully in the 1980s. The kind of frivolous Debbie Gibson songs that made a great target for you were suddenly the target of the songs that were on the radio as alternative rock became a huge phenomenon. How did you feel about alternative rock when it exploded the pop music world in 1991 or 1992?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I was a big fan of alternative music. I was thrilled when Nirvana became a big hit. When they first came on the scene my first thought was that I’d love to do a parody of these guys, but they’re never going to be mainstream enough for me to make fun of. Then when their album went to number one I was thrilled, and thankfully Kurt and the guys had a great sense of humor about the whole thing. I was a big fan; the 90s were a great time in music. I like real instruments, I like guitars, I like the whole DIY aesthetic, and I like actual bands. The whole indie and alternative scene was a lot of fun. It was great to see pop culture take a dip into that area for a while.

JESSE THORN: It’s a very different aesthetic than some of those new wave bands that you talked about admiring like Oingo Boingo or Devo who were often at their core about satirizing things; about having fun and being funny, sometimes in a campy way, sometimes in a satirical way, various ways. Alternative rock was not what you would generally describe as humorous.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Maybe not generally, but they certainly had a humorous alternative bands. There’s a lot of – – I don’t want to give you a laundry list of names, but my favorite bands at the time – – well, just one example, The Presidents of the United States of America. They’re part of the Seattle scene, part of the alternative scene, but there was certainly a lot of humor in their songs. And again a lot of their material was celebrating banality much like my material was, so I definitely found some kindred spirits in that scene.

JESSE THORN: Let’s hear a little bit of Alternative Polka, one of my guest Weird Al Yankovic’s legendary polka medleys of popular music, this if of the popular music of the early 1990s.

So tell me a little bit about what inspires you to create not one of your parodies, but one of your original tunes. Do you usually start with a joke; do you start with a melody?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I usually try to match what I think is a good subject matter for a song with a genre that may actually be completely inappropriate for it. I’ve got a notebook somewhere that has a list of artists and genres and musical styles; one side of a column and a lot of ideas for songs on the other side, and sometimes I’ll draw lines between the two and try to match them up in a way that I think would be a humorous juxtaposition.

The bands are generally bands that I admire greatly, because it would be difficult for me to do a style parody or a pastiche of a band that I didn’t really enjoy and respect because it involves really putting on their skin, really getting into their song catalogue and trying to figure out the idiosyncrasies and what exactly makes them tick, and that involves a lot of research. I generally wouldn’t do that with an artist that I didn’t like.

JESSE THORN: Let’s hear one of those style parodies. This is Pancreas; it’s a song that my guest Weird Al Yankovic recorded in the style of Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys.

Truly a pretty song.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Well thanks! One of the prettier pancreas songs.

JESSE THORN: What is your greatest goal when you’re writing a song? Do you feel like you’re writing a song to be as funny as it can be, or do you feel like you’re trying to do something else?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I think being funny is probably the biggest priority. Some of my songs aren’t laugh out loud funny; some of them are just a little strange or a little quirky. I like doing those as well, but those usually get a reaction kind of like, “That wasn’t funny!” So I always have to remember that I’m supposed to be funny, so that’s probably number one. At the same time I want to indulge my musicality and do stuff that I think people will enjoy strictly in a musical level as well.

JESSE THORN: In the 1990s you started to do parody songs of hip hop records. To that point most of the parodies of hip hop that were out there were – – from the perspective of a person that actually likes rap music – – very disrespectful and ham-fisted and reduced this genre of music to a kind of insulting, childlike sing-song bologna, which spoke to the parodists misunderstanding of it as a thing in the world.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Are you talking about Rappin’ Rodney or Rappin’ Reagan?

JESSE THORN: Exactly. There were dozens and dozens of those records, and I didn’t think any of them were much of anything.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Most of them were based on the joke of, isn’t this funny, there’s a white guy trying to rap.

JESSE THORN: Exactly, so when you first approached hip hop in songs like Amish Paradise, which was the early 1990s, and a huge hit, another huge hit that I remember from my own childhood. What was your perspective on what had been done and what could be done?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I tried to just basically ignore most of those examples that you mentioned. The primary joke was not here’s some goofy white guy trying to do a cool musical genre, I basically respected the music and treated it like I would any other pop song, and tried to emulate the style as closely as I could. I tried to make the jokes be jokes that were contained in the actual lyrics as opposed to “Isn’t this crazy, what I’m doing?!”

JESSE THORN: One thing that I was always impressed by is that you’re really not a bad rapper.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Well, thanks!

JESSE THORN: And rapping is kind of hard; I know that I could not successfully rap. Tell me a little bit about the work that is involved in achieving the level of competence that is needed in order to make a successful parody.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: That’s a hard one to answer because I don’t know – – thank you first, for the compliments, but I don’t know where the skill comes from. I think it comes from a lot of unwarranted confidence in myself and the desire to try anything and keep doing it until I get competent at it. I never considered myself a rapper, but I am a musician so in terms of rap I can figure out, okay, these syllables need to be eighth notes and this one has to be a quarter note, and I figure it out musically and then just give it my best shot.

JESSE THORN: Let’s play a little bit of White and Nerdy, one of your more recent hip hop parodies.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Yeah.

JESSE THORN: That was White and Nerdy from my guest Weird Al Yankovic. Do you like to listen to parody? Is parody a form that intrigues you as a consumer of media?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I try not to listen to a lot of other parody artists. There’s a lot on YouTube, and I’m aware that they exist, but I try not to expose myself to that because I don’t want to be unduly influenced. I try to be aware, just because I wouldn’t want to tread ground that’s been tread before if at all possible. That’s becoming more and more difficult every year given the nature of portals like YouTube. I still enjoy comedy music, I still enjoy satire, but I try not to expose myself to a lot of other actual parody songs.

JESSE THORN: When I was in college one of my professors was Tom Lehrer, who’s one of the great funny musicians, although he recorded only two LPs if I remember correctly.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Maybe three.

JESSE THORN: Okay. He was one of my professors and he was a very funny, very crabby guy. He earned the right to be crabby. In fact, I believe his direct quote about why he never made any more records was, “What’s the use of having laurels if you don’t rest on them.”

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I think he also said at one point that he thought that satire was dead after Henry Kissinger won the Nobel Peace Prize.

JESSE THORN: So Tom Lehrer – – it was a class on American musical theater, and at one point he was talking about song writing and he said that since 1960 there were two song writers that he liked. One of them was Steven Sondheim, you’re going to have a hard time finding a lot of disagreement on Stephen Sondheim, and the other one was Randy Newman. The thing that he liked about Randy Newman was not only that he was funny, but also that he wrote songs each of which had its own interesting perspective, its own little world. I feel like some of the songs that you’ve recorded more recently and released have had a little bit more narrative, a little bit more pathos, even, sometimes. And I wonder if that was a self-conscious choice.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: No, certainly nothing that I’ve done consciously. That’s interesting, but I’ve always been a big fan of Randy Newman, and I admire a lot of the songs, especially the ones that have the distrustful narrator, where he’s obviously – – the real Randy Newman certainly wouldn’t be voicing opinions like the ones in the song, but he has created a character and the song is in the voice of the character. I think a lot of my songs are that way as well. There’s certainly some very questionable people that are the first person narrators of some of my songs, so I think I probably got that idea from Randy.

JESSE THORN: I want to play a little bit of a song that you released on the internet that will, I think, eventually become a part of your new album which is coming out later this year as we record this. It’s called Skipper Dan. It’s a really uncharacteristically sweet, sad – –

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Bittersweet, yeah.

JESSE THORN: –Version of your typical sense of humor, here’s Weird Al Yankovic in Skipper Dan.

Tell me a little bit about what inspired you to write that song about broken dreams.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: I think that I was actually on a Jungle Cruise ride with my family at Disneyland, and the skipper made an offhanded comment about his failed acting career, and a light bulb immediately went on, that’s a whole song right there. I can visualize this sad characters life of broken dreams. Skipper Dan isn’t really one of my laugh out loud funny songs, but I thought it was a really interesting character study, and something that I enjoyed taking on.

JESSE THORN: Were there things that you left by the wayside? Your own dreams that you abandoned in order to pursue this amazing career as a parodist?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Not at all, I’m living the dream. This is it. I can’t imagine anything else I’d rather be doing, frankly. Comedy and music have always been my passions, and I still can’t believe that I’ve been able to make a living at it all these years.

JESSE THORN: Even though the theme of your new children’s book, When I Grow Up, is the panoply of dreams that a child has for his life, of which he obviously may well have to pick just a couple.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: Within the context of Weird Al I’ve been able to not only be a singer-songwriter, but I’ve been able to be a director and a producer and a writer on movies, and I’ve done a lot of things within that context, so I feel like I had a lot of various things going on in my life, just like Billy had going on in his head in the book.

JESSE THORN: Are you surprised that now as you essentially enter middle age you are not only still in the midst of a career, but essentially as successful – – as high in the music industry now as you have ever been?

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: That’s a great feeling, because most artists that have been lucky enough to have a career that’s lasted a few decades, when they do their live show and say, “Here’s something from the new album!” That’s usually the bathroom break, people say okay, be back in 20 minutes. I’m very fortunate that every album that I put out is as vital and as popular as anything in my back catalogue. My last album was ostensibly my most popular album of my career. It’s the first one to chart in the Billboard Top Ten; White and Nerdy surpassed Eat It as being my most popular single, it sold over a million legal downloads and I don’t know how many illegal ones, quite a few I bet. It’s a pretty heavy thing to realize that this far into my career I’m actually sort of peaking.

JESSE THORN: I sure appreciate you taking the time to be on The Sound of Young America, Al. It’s something we’ve always wanted to do; it’s really great to have you on the show.

WEIRD AL YANKOVIC: It’s great to be here, thanks so much.

JESSE THORN: Weird Al Yankovic’s new album comes out this summer or so. His best-selling, yes, that’s right, New York Times bestselling children’s book is called When I Grow Up.

Okay guys, I hope you enjoyed that episode of The Sound of Young America as much as I did. If you’ve been waiting until the show was over to donate, now is the time. Maximumfun.org/donate. Ready? Steady. Go!

In this episode...

Guests

- "Weird Al" Yankovic

About the show

Bullseye is a celebration of the best of arts and culture in public radio form. Host Jesse Thorn sifts the wheat from the chaff to bring you in-depth interviews with the most revered and revolutionary minds in our culture.

Bullseye has been featured in Time, The New York Times, GQ and McSweeney’s, which called it “the kind of show people listen to in a more perfect world.” Since April 2013, the show has been distributed by NPR.

If you would like to pitch a guest for Bullseye, please CLICK HERE. You can also follow Bullseye on Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook. For more about Bullseye and to see a list of stations that carry it, please click here.

Get in touch with the show

People

How to listen

Stream or download episodes directly from our website, or listen via your favorite podcatcher!