Episode notes

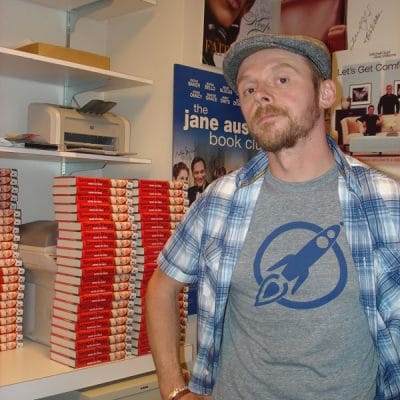

Simon Pegg joins us to talk about nerd rants, his philosophy on zombies, and his close-knit relationship with collaborator and friend Nick Frost.

He’s best known as the actor, writer, and director whose guiding hands have been involved in British TV comedy Spaced and films Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz, and Paul.

His new memoir follows his own journey as the nerdy everyman; Nerd Do Well: A Small Boy’s Journey to Becoming a Big Kid is out now.

JESSE THORN: It’s The Sound of Young America, I’m Jesse Thorn. My guest is Simon Pegg; actor, writer, memoirist, geek. His new book is called Nerd Do Well. It’s the story of how, well, let’s be honest, a nerd did well. And a nerd did well through nerdiness. Almost all of Pegg’s work has drawn on his identity as not just creator, but also fan. He co-created and starred in the British sitcom Spaced, which saw the world of the sitcom, or the romantic sitcom, through a pop culture lens. He made his reputation here in the United States with the hit zom-com, Shaun of the Dead; that’s zom-com, half romantic comedy, half zombie film. He was co-writer and star of Hot Fuzz, which was again, a tribute/satire of the action-comedy, and he recently co-wrote and starred in Paul, which was, again, a sort of half-parody, half-tribute to, in this case, the extraterrestrial films of one Mr. Steven Spielberg.

And how’s this for geek credit: he was Scotty in the reboot of Star Trek.

What binds all of these projects together, of course, is a deep appreciation for popular storytelling, including the kind of genre stories that, let’s just say don’t have the mainstream artistic credibility of 18th century period drama; in other words, they’re geeky.

Simon Pegg, welcome to The Sound of Young America.

SIMON PEGG: Thank you very much. It’s nice to be here.

Click here for a full transcript of this interview, or click here to stream or download the audio.

JESSE THORN: How do you feel about nerd, both as cultural category and as an identity? It’s a big commitment to put it on the cover of your book.

SIMON PEGG: It’s an interesting one. I think the word is ever-evolving and has morphed over the years. It does come from the phrase ne’er-do-well — that’s where the word is derived from — it was just shortening of that, which then became ne’erd and then nerd, meaning someone on the fringe of society. But ne’er-do-well means a sort of criminal, a sort of someone who’s a little bit shady.

Eventually it came to – – and I think it was because of the onomatopoeia of the word nerd, it became sort of someone who is a bit shrimpy and kind of a The Revenge of the Nerds, nerd. The word geek suddenly became okay, which was an enthusiast and a person who liked their stuff, and usually their stuff was sort of rarefied science-fiction fantasy kind of stuff. Nerd recently has been taken back, too. It was also a nice play on words, and I figured, that’s a good title. I took a risk of self-proclaiming my nerdism in the name of wordplay.

JESSE THORN: I interviewed this guy one time who wrote a book about the history of nerd-dom, and I didn’t realize what a contemporary construct it was. I was born in 1981, and so the birth of nerd actually happened in the mid-to-late 70s as an idea and a word, so it’s always existed for me, but that’s something that, you’re a couple years older than me, happened within your lifetime, and it happened within certain things that are still cultural touchstones of nerd-dom, like Star Wars, which you write about in the book.

You did amateur theater and stuff like that as a kid. Did you think of yourself as being a member of a nerd or geek group?

SIMON PEGG: Not really. I think one of the things about nerdiness as it stands now is that it’s more about adults being passionate about slightly infantile things. When you’re a kid and you’re into Star Wars, you’re not a nerd, you’re just a kid. It was kind of very common. Virtually every child in my class had some interest in it, particularly the boys. I think the way that the word has evolved it now means people that are not afraid to pursue infantile regression. You only have to look at what’s on the movie theaters at the moment. The big marquee’s films are all fairly arguable, childish fare. It’s robots and super heroes and comic book stuff. That’s kind of been made acceptable as an adult interest by the transformation of this idea of the nerd.

When I was a kid, it was different. In the mid 70s, nerds were the guys in Animal House and the guys in Revenge of the Nerds, the sort of skinny, dweeby guys with the glasses and the giant underwear shorts who were d-bagged by men with large chest. That seems to be less applicable to that word now. It’s been hijacked.

JESSE THORN: A lot of these nerd stories are kind of power fantasies. They’re stuff that, as you said, comes from kids and adolescents. Kids have no power at all, and adolescents are trying to figure out how to get power and agency in the world. How do you think those stories are different when they’re applied to people who are 30 or 40 years old than when they’re applied to 12 year olds?

SIMON PEGG: You could possibly attach it to this sort of rise of the beta-male. Particularly men as well, although there’s a very thriving female nerd population now, and self-proclaimed and very active. I think possibly what it is, and I’m theorizing on the go here, is that – –

JESSE THORN: I did ask you to come in with a position paper.

SIMON PEGG: If I could just look at my notes…

It’s possible that guys and girls — that were perhaps not at the forefront of dominance in their classrooms growing up — applied themselves in such a way that some of the other bigger, less-intelligent kids did, and are not in a position of power. It seems to me like the world is kind of run by those people now. If you think of – – I can’t imagine Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates, or in the film world, people like Spielberg or Scorsese, being particularly active on the sports field, the kind of place where dominance reigns in the classroom, but now they’re controlling the media output, and with the likes of the first two this silicon revolution.

Now, it’s like they’re the bosses, and now the people who control that means of expression are the ones relaying their fantasies to the world, and that’s what we’re seeing in cinema and literature and comic books and what have you. It’s kind of the fantasies of beta-males.

JESSE THORN: I want to play a clip from the television show Spaced, which features you as one of the stars of the show. Your character works at a comic book store and there are two scenes in succession we’re about to hear. The first one is you telling off a nine-or ten-year-old kid for wanting to buy a Jar Jar Binks doll, and then your boss entering and delivering a stern reproach to you.

I thought this scene was really great because you can feel watching this how real the passion is behind your tirade, and at the same time your character is getting fired by the owner of a comic book store for essentially being too nerdy.

SIMON PEGG: That was interesting. I’d seen the Star Wars Phantom Menace in between seasons; I went to see it in America. After making the first series I had a bit of money for the first time ever and I thought I’d spend it on a pilgrimage to go see the next installment of my beloved story, and obviously, it was hugely disappointing to me and I was pretty angry about it in a way that isn’t at all sad or pathetic.

JESSE THORN: You were far from the only one. I remember that.

SIMON PEGG: Of course. There was a veritable riot, at least in words. I think Spaced I had this math piece in my character Tim, who was essentially a version of me, almost an aspirational version of me in a way. I had a thing about, I’d love to work in a comic shop, I’d like to be a better skateboarder and a better artist. Tim embodied certain aspirational designs of mine, but he also became this wounded spurned lover when it came to Star Wars, and I was able to articulate my feelings about that particular film. When I was delivering those lines to that child, about how stupid he was for wanting a Jar Jar doll, I meant it.

JESSE THORN: One of the interesting things that sort of came out in my mind as I was watching that is the relationship between a geek and the thing that he, typically he, sometimes she, is geeky over is so deep and passionate and personal to that person; it’s about something that speaks directly to their deepest, darkest stuff. But at the same time, if you were a geek, you don’t necessarily have control over that thing, even when that thing is a fantasy about control.

SIMON PEGG: Absolutely, and ownership. That bit in Spaced is as much a satire of my feelings as it is a demonstration of them. It’s funny to me that it made me that upset. It’s funny to me that something like that matters that much to me that it would annoy me, that it would actually impact on the surface of my emotions in such a way that it could change how I felt. It is because these things, we as geeks or nerds or whatever, we latch on to these things and they become our own. Usually in nerd culture, the more underground the better. It’s like people getting into bands when they just started and then dropping them later on when they feel that they’re too popular. I guess even though Star Wars was a global phenomenon, to a degree it felt like this new series of films gatecrashed it and suddenly it wasn’t so special anymore because little, tiny children were endorsing it by buying the merchandise, which kind of slightly diminished it a bit.

JESSE THORN: You’re literally turned in to that little, tiny child in that clip from the show. The little, tiny child runs screaming and crying from the store, and the second part of that clip is you running, screaming and crying from the store.

SIMON PEGG: Because Tim is essentially a big kid. That’s what we are as kind of a – – there’s a whole argument about it. I remember reading at University [INAUDIBLE], I can’t remember the name of the book, but he has a big theory about infantile regression, about our desire to be children. It’s a need that we have to escape the realities of adulthood which is accommodated by the means of production because it suits them to keep us in a state of childishness, and I think it’s true. If we’re permitted to remain children, we will.

If all we’re offered to stimulate us is bangs and flashes and very black and white tales of good and evil, then that’s what we’ll consume, and gladly. That’s why in the book I argue that Star Wars was like that for the post-Vietnam American populate, who were dealing with an awfully confusing situation where the usual goods and evils of conflict were completely blurred, and no one knew who was the good guy. Suddenly, Star Wars came along and laid it all out again in nice, broad strokes, and everyone leapt on it because that’s how they wanted to feel.

JESSE THORN: It’s The Sound of Young America, I’m Jesse Thorn. My guest is actor, writer and comedian, Simon Pegg. Some of his biggest projects have been collaborations with Nick Frost and Edgar Wright. They include the TV show Spaced, the films Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz.

Here’s a clip from Shaun of the Dead featuring Simon and his real-life and on-screen best friend, Nick Frost.

I want to talk to you about your relationship with your collaborators Edgar Wright and Nick Frost, and I want to talk about the films that you’ve made with them, but tell me a little bit first about how you met Nick, who was one of your closest friends as well as one of your closest collaborators, and a big part of this book.

SIMON PEGG: He is, and I’d say he’s my closest friend. I met him at a time in my life when I was too naïve to think that I would make friends again. You think you make all your friends at school — there’s that quote from Stand By Me where Richard Dreyfuss says, “I didn’t have any friends like the ones I had when I was twelve. Jesus, who does?” Well I do, and I met Nick when I was 22, quite by chance, as I suppose any meeting is.

I moved to North London from Bristol where I was at university with my girlfriend, and she got a job at a local restaurant next to the apartment we bought, which was very random. Like in Spaced we looked in that free paper and found a place that seemed right and we got it. She had to get a job and came back from work one day and said, there’s a guy at work, he’s really funny and I think he wants to be a stand-up comic. Can you give him a hand in pursuing that? I was like, yeah, sure. I was a young stand-up at the time, and I was barely experienced, but I was nevertheless more experienced than Nick.

JESSE THORN: You were experienced enough, as you described in the book, to do a complicated routine that involved you dressing as a lifeguard.

SIMON PEGG: Yeah, and carrying a goldfish bowl around. That’s another story, the weirdness of carrying an actual fish around. Anyway.

I set Nick up with his first few gigs and took him out to clubs. We were hanging out and I felt a sort of – – Nick’s 18 months younger than me, and I kind of liked having a slightly paternal relationship with him at that time, because it was like he was a young guy and I was a sort of fresh-out-of-university and all clever and stuff. I took him out to some gigs, and he definitely had a something. He was very, very funny to hang out with. Even though, when he was doing the gigs, he couldn’t quite translate his natural funniness to a performance. His ideas were there, but his delivery was a little uncertain and, like me, he doesn’t like something if you can’t be good at it straight away, so after about ten gigs he quit and went back to waiting tables. By that time, him and me were thick as thieves and we’d been spending loads of time together.

When Jessica and myself came to make Spaced, we decided to write a part for Nick, and it was like, we’ll tell the producers he’s an actor and see what they say. There was another guy in our version of SAG, which is called Equity, called Nick Frost. They looked him up on the database, whatever it was in those days, Rolodex. They went yeah, okay, fine. So we kind of smuggled this civilian into the world of acting and it was Nick.

That was all he needed, really. I don’t claim any more responsibility for his career than that, because if he hadn’t been able to do it, he would have vanished very quickly, but he’s very good, so he’s still here.

JESSE THORN: Where did the voice of Spaced, that was this collaboration, essentially between the four of you, and is textually dense as a sitcom could be – – as I said, sort of about your character’s relationship to popular culture as well as their relationship to each other and the relationships thereof. Where did that voice come from, do you think?

SIMON PEGG: First and foremost, it was a collaboration between Jess and myself. We’d met on a sketch show and then I’d gone on to work on something that Edgar directed – the first time I ever worked with Edgar — and we needed a female for the cast, and I immediately suggested Jess, because she’d impressed me so much. Jess and I worked very well in this show called Asylum — no one saw it — it was a little cable odd-show about an insane asylum full of comedians. We were offered a show — a producer from Paramount Comedy Channel was moving to a large TV network — and had offered us this vehicle. We, in a very naive way, said yeah, we’d like to do that, but we want to be able to write it, we want control. That was because all the 20something sitcoms of the age that were out at that time, things like Coupling and Friends, and there were other shows called Game On and there was another, all didn’t say anything to us about our lives. There was nobody in those shows we could relate to whatsoever, it was just this odd world of good looking people drinking and wearing strangely adult clothes.

We wanted to write something that was from the heart. Jess had this whole thing about trying to find an apartment in London, and I had this whole thing where I had just broken up with a girl. I kind of felt like I wanted to write something from the point of view of a wounded soul, and both of us wanted to channel in our love of popular culture and have it be almost as though Spaced is Tim and Daisy’s account of their life, and everything you see being represented is how they would describe it. It’s like a metaphorical layer that you see when you watch the show. If they try and break into some sort of building to get the drawing back, they immediately picturing it being like the Matrix, and that’s kind of what Mike dug.

The only person we could think of to direct it who could possibly do something with it was Edgar. I just worked with him and had been amazed at his talent, it was extraordinary.

JESSE THORN: I want to ask you about the idea of the wound in your character; the hurt in Tim. Brian Posehn, who’s a stand-up comedian and has been a guest on this show in a couple of times, named one of his albums Nerd Rage, and I think there’s this part of geekiness that is motivated forward by a woundedness, sort of like the ferociousness of a wounded lion or something like that. Does that resonate for you – the idea of there being a little bit of smoldering hurt behind the especially geeky aggression?

SIMON PEGG: It’s an interesting point actually. I like Brian, I think he’s very funny. I think there is an anger in nerds. You see it on the internet, there’s a lot of hate on the internet. There’s a lot of people who decry things just for the enjoyment of experiencing anger. I think possibly it’s related to the fact that maybe nerds are people that have escaped into a sort of fantasy world because the real world is not so nice for them and maybe they’re mad about that. Maybe they’ve carried that sort of rage into their second life, and I don’t mean the computer game.

Tim is definitely – – he’s been wounded by his girlfriend, so he’s angry about that. He’s a frustrated artist who should be doing a lot better than he is and he’s angry about that, he’s angry with George Lucas. I think it’s all probably projection; he’s projecting other inadequacies onto these things because it’s easier to get angry about them than the truth maybe, which is that he’s an underachiever or that he’s a coward or that he couldn’t keep his girlfriend happy. The other things become the focus of his rage. That make sense to me.

Star Trek is very evidently one of the top nerd fascinations because it is a world that offers inclusion for everyone. It’s a world where there is acceptance in a future where there is – – I know there are still throw downs with various nefarious races, but generally speaking, it’s a kind of utopia, that sort of federation world. I think people long for that a little bit, it’s a society where people will be accepted. That’s the reason it attracts people who are perhaps on the fringes of the mind stream because they see it as a world that they wouldn’t feel crap about themselves in. That would make anyone angry.

JESSE THORN: It’s interesting that people see Star Trek as something that they can be a part of in a way that with Star Wars they wouldn’t. They might identify with Han Solo or Luke Skywalker or something like that, and imagine themselves as that, whereas I feel like people who are into the world of Star Trek imagine themselves as just one of the people that lives on that ship in that world.

SIMON PEGG: Absolutely, and I think that’s because Star Wars is more aspirational and the characters in it are more archetypal, they’re more that kind of – – Han Solo is that smooth hero that you want to be or the boy that does good in Luke Skywalker or the Princess or the father, all these archetypes that pop up in that story and make it what it is; whereas, Star Trek is this proposition, this world where all these people just coexist and you could be one.

Weirdly enough, tying this all together, I think that’s one of the reasons that zombies are so popular. That world offers a survival situation where you stand a chance. That’s why I get so bummed about fast zombies because it takes a little bit of that away. If anyone is careful and does the right thing they could probably do okay in a zombie apocalypse. You don’t have to be the terminator in that situation, so it offers a fantasy world where a normal person could possibly survive. I think that’s similar with Star Trek.

JESSE THORN: In Shaun of the Dead, which you co-wrote with Edgar Wright, it is essentially a collision between the zombie film and the romantic comedy, and it’s also a collision between the extravagance of a world being taken over by zombies and the reticence and reserve that is typical of England, indeed to some extent, Britain. I want to play a scene that is very exemplary of that from the film.

In the scene, your character is realizing that his step father may have been turned into a zombie.

So, zombies are this really powerful thing, and have always been a very American thing. I know that you have passionate opinions about the difference between the fast zombie and the slow zombie, the slow zombie being the classic zombie that you can outrun but goes on forever. One of the things that’s interesting to me about the difference between those two kinds of zombies is that a slow zombie feels like a human being that is stripped of will; a slow zombie is a human being that, and I’m not super zombie guy, so you can feel free to tell me that I’m an idiot, but it feels like a human being that doesn’t have any agency at all. Just moves not only in this herd, but inexorably forward towards a death that will never come because they’re undead. A fast zombie is just an evil creature. A fast zombie is actually making choices in a way that a slow zombie isn’t.

SIMON PEGG: Exactly, I think that nails it. A fast zombie suddenly has an agenda and has momentum and all those things remove the tragedy from the zombie, which I think really makes it an interesting monster in that a human being stripped of will, as you say, is actually deeply sympathetic. Your enemy in that world is yourself. They are a walking, groaning metaphor for our own end. They are inevitable, they come at you and no matter how much you try and avoid them with fitness and good food, they just will get you in the end no matter how rubbish and silly the death is, you’re going to die. They are the walking dead, they are the walking representation of our greatest fear, of our deepest psychological problems are caused by this thing.

In that, they are far more interesting than any other movie monster. I don’t really feel sorry for Dracula even if he has a crush on Mina Harker. I don’t particularly pity werewolves when they’re tearing people apart because they’re our bestiality and they’re – – but there’s something interesting about zombies in that they’re just a bit sad, and you feel like – – that’s the great thing about Romero’s films. He managed to create these tragic heroes out of zombies, particularly in Day of the Dead, where you actually end up rooting for the zombies because the human characters are so loathsome and you kind of want to see them die. You cheer on Bob who’s this fantastic creation that Howard Sherman played, this amazing childlike born-again human being who’s figuring out how to listen to music and shave and do all these things. At the end of the film when he manages to slip his bonds, you’re like, “Go Bob, Go!” And yet they’re supposed to be the bad guy in the film. It’s a really nice dichotomy. It’s interesting.

The minute they start growling and running and screeching like Velociraptors all disappears, it just becomes about thrills. It’s like shouting, “Boo!” It’s as sophisticated as shouting, “Boo!”

JESSE THORN: You’re a big zombie enthusiast I think, as is evident by the fact that you made this feature film with that subject and also your opinions as just stated. Do zombies scare you for real as well as fascinate you?

SIMON PEGG: They do. I must admit, I still dream about them. I still have these recurring dreams about being in that situation which stem from those early movies, specifically Romero’s first three zombie films. He essentially invented that particular strain of this mythology. He combined it with a sort of cannibal thing that was going on at the time in the 60s, there was a bit of interesting cannibalism. He kind of added a “soup’s on” of the vampire viral communication thing, little bit of this, little bit of that.

The human flesh thing – – zombies were originally a sort of Haitian witch doctors who would essentially subdue people with digitalis until they appeared to be dead and then they’d be buried, and then they’d be dug up and put to work in fields as cheap labor, and then relatives would be walking along and see their dead uncle picking cotton and think, “Oh, it must be a zombie.” I don’t know what the truth of that is, but that’s the mythology that it came from. Romero cooked up these extra ingredients, and now we all know the zombie as being this – – in fact, it was Dan O’Bannon that invented the brains thing, everyone goes, oh yeah, brains. That wasn’t in Romero’s original thing, in Romero’s thing they eat everything, not just the brains. Anyway, I’m getting super nerdy.

It’s so fun to talk about something as trivial as this in such depth. I think it’s fantastic, that’s why I love film theory. It’s fun.

JESSE THORN: Does it actually seem like it’s trivial to you? Is it different from – – do you think it’s fundamentally different from another thing that I think people would say is not trivial, like, I don’t know, like James Joyce or Shakespeare or something like that.

SIMON PEGG: I think ultimately all art is trivial.

JESSE THORN: That’s what makes it art and not work.

SIMON PEGG: Yeah, it’s expression. Whether you’re discussing themes in Wuthering Heights or themes in Dawn of the Dead, I think both those things have equal weight, and if you say they don’t then you’re being slightly snobby. High art is no more important than low culture. The expressions of popular culture is just as much an expression of our deep psychoanalytical problems as Bronte and Shirley and all that kind of stuff. I think it’s less important than us sitting here talking about a cure for cancer, having a productive conversation about a cure for cancer is far more important really.

JESSE THORN: By the way, we do have a cure for cancer, but we’re not going to talk about it. We’re here to talk about zombies and stuff.

SIMON PEGG: I’ve got this test tube in my pocket, but we need to talk to you about…

It’s important. It’s good for the brain, whatever you’re talking about in terms of theory. It’s a nice workout, whether it’s trivial or life changing.

JESSE THORN: The films that you and Nick Frost and Edgar Wright have made, as a team, and I’ll even include Paul in this, despite the fact that that was directed by Greg Mottola, these are films that are in part pastiche, in part parody, in part celebration of these genres in. In Shaun of the Dead it’s the romantic comedy and the zombie film, in Hot Fuzz it’s the classic, quaint English film combined with the classic outlandish American action movie, and Paul is this combination of nerd love letter and friendship film with the kind of magic and wonder of the kind of Spielbergian fantasy, sci-fi type thing.

Tell me about how you ended up working so much on these movies that in a way had one foot in their genres and one foot out.

SIMON PEGG: I think because most likely we were making the films that we like to watch. We are part of that generation, the post-Star Wars generation who grew up on very populist culture, who grew up after that shift in cinematic when it became more about – – when it did start to get a little younger-skewed. Before Star Wars, it was all Bonnie and Clyde and the Corleones and Popeye Doyle, all these characters that were very adult and dark and amoral, Travis Bickle. Then suddenly it was all about Luke Skywalker and Indiana Jones – – not together though, that would be a great team up.

I think me, Edgar, and Nick all grew up watching those films, and our artistic output as a result are us recreating those in the same way those kids made Raiders shot for shot on video. That’s kind of what we’re doing because it’s what we really know and what we have a passion for.

JESSE THORN: That’s kind of a geek thing. To know something really well so that you can recreate it, but then there’s an additional thing too.

SIMON PEGG: Yeah, and also there’s the fact that we also come from a comedy background, so these things aren’t just iterations of what’s come before. We’re trying to use those styles as metaphors to say other things. We’re not making any great political statements, but Shaun of the Dead was very much about the anonymity of living in a city where you don’t take any notice of anyone around you, it was about growing up, it was about responsibility.

Hot Fuzz was about how sometimes you have to switch off your brain. It was a clarion call to brain deadedness. Angel doesn’t become a sort of fully rounded figure until he embraces gratification films, and Paul was probably a reflection of mine and Nick’s journey to America. Finding ourselves working with the likes of Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson and Quentin Tarantino — we made this pilgrimage to this fabled land that we’ve looked at all our lives and these monumental figures stepped out of the shadows and they were just like normal guys like Paul did. Paul is probably, in some respects, the embodiment of Spielberg himself, when we met him and found him to be this regular dude.

There’s always more going on than us just blindly firing entertainment at people. The films do say – – they work on deeper levels than perhaps some other films do. I don’t know.

JESSE THORN: Simon, I sure appreciate you taking the time to be on The Sound of Young America.

SIMON PEGG: It’s been a pleasure.

JESSE THORN: Simon Pegg’s new memoir is called Nerd Do Well: A Small Boy’s Journey to Becoming a Big Kid. He’s featured in, among other things, the next Star Trek film that is probably as secret as the first one, which is so secret that my friend who worked on it was talking about ferrying people to the set through secret tunnels.

SIMON PEGG: True.

JESSE THORN: The next Mission Impossible film, the Steven Spielberg Tin Tin film through some kind of robot avatar, and of course, his films and the television show Spaced are available on DVD. Thanks again, Simon.

SIMON PEGG: Thank you.

Our transcripts are provided by Sean Sampson. If you’re interested in contacting him for transcription work, email him here.

In this episode...

Guests

- Simon Pegg

About the show

Bullseye is a celebration of the best of arts and culture in public radio form. Host Jesse Thorn sifts the wheat from the chaff to bring you in-depth interviews with the most revered and revolutionary minds in our culture.

Bullseye has been featured in Time, The New York Times, GQ and McSweeney’s, which called it “the kind of show people listen to in a more perfect world.” Since April 2013, the show has been distributed by NPR.

If you would like to pitch a guest for Bullseye, please CLICK HERE. You can also follow Bullseye on Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook. For more about Bullseye and to see a list of stations that carry it, please click here.

Get in touch with the show

People

How to listen

Stream or download episodes directly from our website, or listen via your favorite podcatcher!