Episode notes

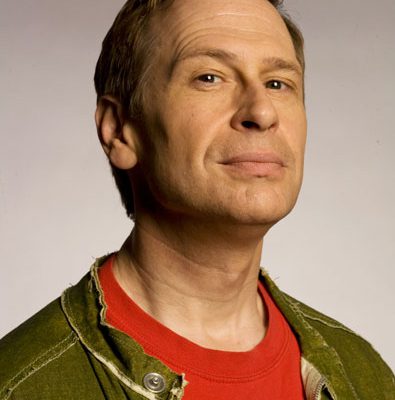

Scott Thompson is best known for his work in the sketch group The Kids in the Hall, whose TV show began airing on Canadian and US television in the late 80s and early 90s and continues its presence today. The all-male Kids in the Hall are renowned for their bizarre, compelling sketch comedy and portraying both women and men with equal aplomb, and Scott Thompson himself has played a variety of beloved characters from the Queen of England to the over-the-top Buddy Cole to the humble, everyday yes man Danny Husk.

Danny Husk is the inspiration for one of his newest projects, a series of fantasy adventures in graphic novel form. The first of those is Husk: The Hollow Planet.

You can find more from Thompson at his podcast Scott Free and website, NewScottLand.

JESSE THORN: It’s The Sound of Young America, I’m Jesse Thorn. The Kids in the Hall are one of the most beloved sketch comedy groups in the world. From their roots in the rock and roll scene of mid-1980s Toronto, through their television program in Canada and the United States and through today, they’ve been known for some of the weirdest, most bizarre, compelling, hilarious comedy that anyone in the world has to offer.

One of the most singular of their singular members is my guest today, Scott Thompson. The Kids were known for their weird, strange comedy. But one of Scott’s most famous characters was Danny Husk, a man whose only weirdness was how banal he was. In this clip from the kids in the hall TV show Danny Husk is sent by his boss on a woodland retreat to find his inner warrior. The retreat leader is played by fellow Kid in the Hall Kevin McDonald.

So it’s pretty interesting that Scott chose Danny Husk to build a graphic novel around; not just any graphic novel, but a fantasy graphic novel called The Hollow Planet. That book is in stores now, and Scott Thompson is with me today. Welcome to The Sound of Young America, Scott.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Thank you very much.

Click here for a full transcript of this show.

JESSE THORN: I was reading about your early life – –

SCOTT THOMPSON: Can I deny it now?

JESSE THORN: The impression that I got, and it wasn’t based off a lot of data points, but some data points, is that post-adolescent Scott Thompson was just wildly out of control in every way.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yes. That would be a good guess, yes. That is true. Yeah. Wildly out of control.

JESSE THORN: Were you a social kid, were you a jock, or were you – –

SCOTT THOMPSON: I was a social kid. I was one of those kids that got along with everyone. I could basically go from every group; from the stoners, to the prefects, to the – –

JESSE THORN: What is a prefect?

SCOTT THOMPSON: What do you call that?

JESSE THORN: I don’t know. I don’t know what that’s called. Is that Canadian high school slang?

SCOTT THOMPSON: The browners?

JESSE THORN: You are just saying words that have so little meaning. You might as well just be saying the bamboo kids.

SCOTT THOMPSON: The bamboo kid, you’re the bamboo kid!

JESSE THORN: Sure. You know, slow cookers.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Slow cookers, yes. The crockpots, you call them crockpots here.

So I was a crock pot, I could go from the crock pots to the slow cookers. I was very social and I got along with everyone because I think that might be a very classic trait of gay kids; particularly back then, now, maybe not so much. They’re more accepted, they don’t have to develop those kinds of skills the same way that we did.

JESSE THORN: What changed when you left and went away to school and eventually were expelled from the theater program at your college for being disruptive?

SCOTT THOMPSON: It was like I could finally be who I was. I wanted to be a dancer growing up, and there was no way on earth that could ever have happened. I’d been accepted to journalism school, Carlton in Ottawa, but I secretly applied to York University for theater, and I also got accepted there. My parents didn’t know that, they thought I was going to be journalist. I told them I was going to theater school and they hit the roof. I might as well have said that I was sleeping with a big black man – – that came later.

Then I went crazy. It was the moment I went to theater school when they gave me my tights. I looked so good in tights, and I went – – this is the look that I’ve been meaning to rock my whole life. And that was it.

JESSE THORN: When you say you went crazy, you were too much for theater school – –

SCOTT THOMPSON: I was thrown out of school, yeah.

JESSE THORN: Which takes some doing.

SCOTT THOMPSON: And out of theater school. The funny thing is I had pretty good academic marks.

JESSE THORN: What kind of acting out did you get involved in that led you to get – –

SCOTT THOMPSON: All my improvs turned violent, that’s a lot of it. Everything would end up with me fighting someone.

JESSE THORN: That’s like the one thing you’re not allowed to do.

SCOTT THOMPSON: I know! My friend showed me Rupaul’s – -what’s that?

JESSE THORN: Drag Race.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Rupaul’s Drag Race last night and one of the queens picked up another queen and through him to the ground like a Mexican wrestler. He was thrown out like – – and I just thought that’s the type of drag queen I would have turned out to be. I was a little – – yeah. I was very insubordinate to the teachers, and I was very mouthy. I didn’t realize that it was possible that I could be a comedian, and I think that I didn’t understand that that was an option. I thought comedians talk about their life; I can’t talk about my life, therefore, I must be an actor and act other people’s lives.

JESSE THORN: When did you start doing comedy?

SCOTT THOMPSON: I started doing comedy in my third year of university; I went to the Banff School of Fine Arts for musical theater. While I was there – -for a summer program – – I did one night of standup comedy, which was just a disaster. After university I spent a couple of years trying to make it as a legitimate actor. This is the straight theater – – you know, an actor. It was about my second year out of university I went to a midnight show at a place called the Poor Alex with my friend Darlene. She said there was a comedy troupe there that I had to see, and I was like okay. I went, it was the Kids in the Hall, and it was the old Kids in the Hall when there was eight of them. They were a group from Calgary and a group from Toronto, they would come together and there were eight of them. It was love at first sight. I saw them and a voice in my head said, You’re going to be in that group.

JESSE THORN: This was a time when, at least in the United States, I don’t know the Canadian comedy scene that well, when club comedy was just absolutely exploding.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yes.

JESSE THORN: With the Paula Poundstone’s of the world doing huge theater gigs.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yeah.

JESSE THORN: I don’t know who else is a good example…your Richard Jennings.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yeah, stand-up comedy was very big.

JESSE THORN: Your stand-up comedy boom.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Sam Kinison. I remember the people loved that.

JESSE THORN: Yeah, people loved Sam Kinison. I remember once talking with your Kids in the Hall cast mate Dave Foley about Kids in the Hall and the early days of the Kids in the Hall. He seemed very proud that the Kids in the Hall were as much a part of the kind of alternative rock scene.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yes.

JESSE THORN: And the punk scene as they were part of any kind of comedy world.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yeah, that is kind of true actually. We were because sketch comedy – – maybe stand-up at the time was having a moment, but sketch comedy was pretty stale. Pretty frozen. It was Second City, basically, and nothing else. Then we came along, we started performing in a rock club. We were in a venue that wasn’t really known for sketch comedy at all, and we were the only people that did it, and everybody that did sketch comedy – – and there weren’t many people – – everybody was trying to get into Second City, that was basically what everyone wanted to do. We were the anti-Second City. Everything that they did, we did the opposite.

We really were about destroying everything. We were young; we were very young. We wanted to bring it down, man!

JESSE THORN: It’s The Sound of Young America, I’m Jesse Thorn. My guest is Scott Thompson, a member of the Canadian sketch comedy group the Kids in the Hall. In this scene from their early 90s television program, Scott plays a loopy version of the Queen of England.

Let’s talk a little bit about the Kids in the Hall. You had a regular stage show in Toronto. How did that regular stage show turn into something that became a television series?

SCOTT THOMPSON: One of the things – – we were very lucky that we weren’t discovered right away, so we had years to develop. We would do a show every two weeks, all new material. We just kept doing it. Every two weeks we’d write a whole brand new show, we did this for quite a while, and then one day – – I’m not exactly sure who – – it might have been Martin Short, it might have been Katherine O’Hara, it might have been Dave Thomas.

JESSE THORN: It was a legend of comedy.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yeah, it was a legend of comedy that saw us and told someone – –

JESSE THORN: Might have been Bill Cosby, could have been Mark Twain.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Could have been Mark Twain. It’s definitely Mark Twain. Oh, I wish it had been. Then we got discovered and – – the SCTV people started talking about us, and then it got back to Dave Thomas who was married to Pamela Thomas and she was an agent at the time and her partner was Diane Pauly who is Sara Pauly’s mother. They came and saw us and signed us as managers, Pam and Diane. Then we did this show at the factory theater lab in Toronto, and it was the first time we wrote everything down and we actually rehearsed it and we got a band; we got The Shadowy Man to do this run – – we did a couple of weeks run, and it was a big deal. We sold out, everybody in Toronto came. And then I think it went from Dave Thomas – – it kind of went, it’s a Canadian telephone, it went from Dave Thomas to Dan Aykroyd to, I think, Lorne Michaels. Lorne Michaels was coming back to Saturday Night Live after going away for a few years and he was scouting, so he came to Toronto to scout. He heard about us, and then they asked us if we would do a showcase for them. So we did a showcase at the Revelry, which was the club that we always performed at, and it was a big deal. Everybody in comedy came to that show, it was lined up around the block and people were lined up all day for it. We did a very, very wild, very undisciplined, crazy – – kind of like self-destructive show. We did a lot of what was new material; we did all this new material. We had no idea, but it was a really wild night and that was it. Lorne said I really want to help you guys get a TV show, and it all came from that night.

JESSE THORN: I want to talk a little bit about some of your characters on the Kids in the Hall. Probably the one that you’re most identified with is Buddy, who is a lush, super femme lounge lizard. At the time there just weren’t a lot of portrayals of gay guys who were gay, where that was part of what they were.

SCOTT THOMPSON: No, none. Very rare. Very rare.

JESSE THORN: Were you self-aware about that? Did that make you feel weird about the whole thing?

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yes, I was very aware that I was out there almost alone, and I knew that I was breaking new ground which can be very exciting, but also can be very painful. I was shocked at the negativity that I got from people, particularly gay men. I got an awful lot of grief from gay men during that time.

JESSE THORN: Let’s hear a little bit of my guest Scott Thompson doing Buddy on the Kids in the Hall.

I think there’s an argument that can be made and certainly was made at the time that it plays into this broad gay stereotype of what a femme/queenie gay guy is like. But on the other hand, I grew up in San Francisco. I knew a lot of pretty queenie gay guys, and they were pretty funny, and they were aware of their funniness, too, but it is a cultural group.

SCOTT THOMPSON: True, but they’re usually the ones who were most upset. It was mostly really queenie guys that were most upset with me. They were like, I can’t believe that you’re always playing gay men like that; I think it’s very insulting and stereotypical. I would be like, why don’t you play your voice in a tape recorder and listen to it, because they’re ridiculous. People were in denial. It was such a polarized time. AIDS was ravaging the gay community, so there was no room for humor. Everything was so deadly serious and earnest and it was life and death, and I think I was seen by a large proportion of the gay community, particularly the Mandarins – – and I love to use that word – – who lorded over the movement as sell out, or the Uncle Tom, or the enemy. To this day it’s still painful for me, because for me I’m like, wait a second, what’s wrong with being effeminate, number one, and number two, lots of gay men are effeminate! It’s crazy! No matter how many weights you lift, you still carry your books like a girl. Grow up! Get a grip! Accept it! I think people were in such a – – it was such a terrible time that Buddy Cole was seen as the enemy. At least Buddy is sexual, he was not neutered, he was never a neutered gay guy. And he was smart! He’s smarter than I am. That queen up until then – – they were always stupid and you laughed at them, and you never laughed at Buddy, Buddy was always in control. He was an alpha queen. I couldn’t understand it; to this day I think they were dead wrong.

JESSE THORN: One of your characters that you played over and over on the show is also the protagonist of this graphic novel that you’ve just written called Hollow Planet, and that’s Danny Husk. In a lot of ways, Danny Husk is the uber straight, white, heterosexual, middle-aged, middle-classed, he is the most – –

SCOTT THOMPSON: Absolutely middle-character.

JESSE THORN: He’s like banality personified.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yes, yes. He’s as much of a – – I’m as much Danny as I am Buddy. I came up with Danny – – I remember it very distinctly how it was born. I was with Dave, and I said, Look Dave, I’m over here. And he said, well, I’m over here, Danny. Well, I’m gonna walk over there. Look Dave, I’m now over here. And that was it, he was born. I just realized, oh, that’s it. We all had our business person persona, and the first time I rocked that persona was in a scene called the joy makers, where we throw a surprise party for one of our business colleagues who happens to actually be there, and that’s where Danny – – it was just my way of, I was satirizing my brothers and my father and basically fighting the super straight guy in me.

It’s interesting, because in the 20 odd years that I’ve been doing Danny Husk, that straight white male has gone from the top of the pyramid to the bottom. In many ways I think straight white males are in many ways today in as much danger as the Siberian tiger.

JESSE THORN: I certainly feel that way.

SCOTT THOMPSON: I worry for them tremendously.

JESSE THORN: We appreciate your concern. I speak on behalf of the straight white community.

SCOTT THOMPSON: I worry for the state of masculinity in North American culture. I think it’s in grave danger.

JESSE THORN: Sadly I can’t speak that well for masculinity. Straight white males, yes. Masculinity, ehhh….

SCOTT THOMPSON: That’s one of the things I love about Hollow Planet. I think the paradigm changed years ago but people aren’t quite there yet. People still think, oh, the straight white male, he’s lording it over us. That’s such bull. That’s not true at all. That’s maybe 25 years ago, but now? No way. The straight white male is more likely to be a straight white female in a power suit than it is an actual straight male. Or a gay guy.

JESSE THORN: This character started off in this sort of family of Kids in the Hall characters that were middle class, upper-middle class people that were so – – I mean, his last name is Husk. And they were so empty that they would essentially walk into each other if you didn’t grab them by the shoulders and turn them in a different direction.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yes, yes. Those were business men, we played them almost like they were robots.

JESSE THORN: But with lower than robot level of intelligence.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Absolutely. Danny is not the swiftest grape on the vine.

JESSE THORN: It’s very interesting that you – – In Hollow Planet, which is my guest Scott Thompson’s new graphic novel, it’s sort of like a Conan story. It’s a very classic fantasy type story that starts with a guy who’s just a put upon middle aged guy with a moustache. How did you come to find the heroism rather than the satarize-ability in that?

SCOTT THOMPSON: Twenty years ago I probably would have written a different story, and it would have been much more mocking Danny. Why I chose Danny for the protagonist of my first Graphic Novel is because – – it was ten years ago when I started to work on this, and I decided – – there are three books, this is only the first one. I thought to myself, I realized that I was in a box, that Hollywood would never see past my homosexuality. That I would always be seen as the gay guy. We need a gay character, let’s get Scott Thompson. It’s embarrassing and boring. I realized that I was not really being seen as an actor any longer, I was being used as a tool for people to show their liberal credentials. And I thought, do that on your own time. I’m a performer. Hire me for a performer. Don’t use me to show that you’re cool. Or that I think gay people are great! It was so boring the characters that I play, these neutered nanny figures.

And so I thought, what character of mine that is the furthest away that will get me out of this box, and it was Danny. I thought, I’ll write a story for Danny. Everybody can relate to him. Everybody can feel superior to him, he’s an everyman. You can go, well, I’m not as dumb as Danny. What I liked about the heroism in Danny is his dogged nature. I realized that there is something about Danny that is so likeable because he just moves forward. Whatever happens, he goes, Well, you just put your foot forward and keep moving. He never complains and never whines and just whatever happens, he accepts it.

JESSE THORN: Including in the book becoming a slave. He says, well, I’m gonna make the best of it. Is that a lady or a fella whipping me? I’ll try and enjoy it.

SCOTT THOMPSON: That’s it. And I thought, that’s funny! Then I thought, okay, I knew who I was going to write about.

JESSE THORN: It’s interesting that you have described this character as the character that always puts one foot in front of the other; that always moves forward, because over the past few years of your life you’ve gone through these incredible, tremendous struggles personally and with your health. You were diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma if I remember correctly and had to do some aggressive cancer treatments with that. Your older brother committed suicide.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yes. Younger.

JESSE THORN: Younger brother, excuse me.

SCOTT THOMPSON: It’s alright, my older brother’s going, wait, I’m dead? How long have I been dead?

JESSE THORN: Also, why am I listening to this show?

SCOTT THOMPSON: Young America, is it in heaven or hell?!

JESSE THORN: Did having those incredible difficulties change your perspective on what you wanted to do with yourself creatively? Was that, for example, part of the impetus of not just wanting to find a way out of just being the gay guy?

SCOTT THOMPSON: Well, no, because that was ten years ago. I wrote this originally as a screenplay and I peddled it for years to different studios and then everybody said, we love it, it’s incredibly original, we’ll never make it.

JESSE THORN: Flying mastodons are expensive to put on.

SCOTT THOMPSON: They really are, they’re telepathic, too. I would keep returning to it and going, I love this story; I have to get this story out. It’s the big story that I want to tell, it’s my Lord of the Rings. I want to tell this huge story. I had to do it. And then it was a couple of – – when I got diagnosed with cancer, it was just before I got diagnosed with cancer, it was about three years ago, I took it around and thought, oh, it would make an amazing graphic novel! They’ll never make my movie, so I was going to turn it into a novel, and then I thought a graphic novel. I pitched it to many companies and they all loved it, but Frozen Beaches, the company I went with because I like the guy Stephan Nilson who was the president, and he took me to Comic Con, so you dance with the one that brung ya.

We did this, and just as we were starting to adapt it, I got sick and everything changed. But the funny thing is, I worked on that book all through my illness, and it was one of the – – the interesting thing is, I was diagnosed in April 2009, so almost two years. I’m cured, by the way. There’s no question that was the worst year of my life, yet at the same time that year that I was going through chemotherapy and radiation and fighting for my life was also the year that I put out The Hollow Planet, and the Kids in the Hall had a comeback series.

It’s hard for me to believe that a year could be the worst year of your life, but also have elements in it that are wonderful. My illness truly – – it was hard, there came a time when I couldn’t work on it. It was all done online, too, all the collaborators, we all worked online, and there came a time when I couldn’t do it. But I kept coming back to it. It was always something that kept me going, because I would go like, I know it seems I have got nothing in my life, but I’ve got The Hollow Planet, and then I started to look at the story of The Hollow Planet, and I realized that there were things in it that happened to Danny, like Danny’s life systematically is destroyed. Everything that he loves is taken away from him, and I realized that it was my own life; that I somehow had been subconsciously writing about my own life that hadn’t even happened yet.

I don’t know how that is, I can’t really explain creativity sometimes. I think there’s magic and ironically the book is about magic. It was the most profound – – and then what I would say to myself was, when I was really in despair, I would say, Danny wouldn’t give up. Danny loses everything, even his moustache for God’s sake, and he comes back stronger than ever. So I would say to myself, you’re going to be just like Danny. You will come back. They will take you to the edge of death, and then I will come back stronger than ever. That gave me enormous – – and also when I was making the kids in the hall series, the same thing. There was a character in the show that I really identified with that was marked for death but doesn’t, he cheats it. Those were the two people. His name was Krim, he’s the native guy. Krim was me and Danny was me and I would hang on to those two guys and go, I’m them. They’re once marked for death, but doesn’t die, and the other one loses everything but comes back stronger, that will be me.

I remember very clearly, it was about my third treatment when things were starting to really tumble. It’s just horrible what they do to you. I had lost all of my hair, and suddenly the pictures started coming in online from my artist Kyle Morton, and they were me as Danny with no body hair. It was just profound to me. It made me cry. I remember looking at them and weeping because I looked at those pictures and it’s me looking back at me. I wrote that ten years before, and I would look and go, how did I know? That was when I said to Stefan – – I was also getting really sad, I said I can’t work right now, it’s freaking me out to see my face. He’d drawn me the way I really was, the way I was looking at that time. I don’t know. Sometimes I believe that this book – – this might seem crazy, but this book had to come out. This whole story had to come out. It’s almost like I knew what was going to happen to me, and that I was somehow preparing so that when it did happen to me I would have something to hold on to. It’s like I built an airbag ten years before an airbag was invented, and then ten years later I had the accident, but I’d forgotten to put the airbag in.

JESSE THORN: The Kids in the Hall had this really tempestuous history. It was a group that was, form what I can tell, even at its peak founded on conflict; forged in conflict, you might say, and was very decidedly broken up to the point where you weren’t really speaking with each other for five or six years.

SCOTT THOMPSON: That’s right.

JESSE THORN: But that brokenupness is now in the past, you did some tours in the 2000s and then this mini-series that ran on IFC here in the States. I wonder what role being part of this group of artists that you’ve been in on and off now for more than 20, 25 years or so.

SCOTT THOMPSON: It’ll soon be 25 years.

JESSE THORN: What role that has in your life now, as a 51 year old man?

SCOTT THOMPSON: It’s still a huge part of my life. Dave did standup last night, I didn’t go but I was going to go see him. I will see Dave this week; we’re going to be doing some gigs together. I’m going to see Bruce next week. We’re very tight. We’re brothers, and we’re in it for life. It’s the only relationship that I’ve ever really made work. In a strange way I’m married to four straight men. Nothing can break us apart now. It’s like we did everything in our power to destroy it, and we couldn’t, so we just finally decided, eh. Let’s just let it live. I would love us to do another tour, I’d love us to do another series, we’ll see what happens. There has to be more interest I think, for that to happen.

JESSE THORN: Scott, thank you so much for taking the time to be on The Sound of Young America.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Thank you very much, Jesse.

JESSE THORN: Scott Thompson is a founding member of the Kids in the Hall. His new graphic novel is called Danny Husk in The Hollow Planet. He’s also the host of the very funny podcast, Scott Free, all of which you can find at his website newscottland.com.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Scottland has two Ts.

JESSE THORN: Let’s be clear.

SCOTT THOMPSON: Yes.

In this episode...

Guests

- Scott Thompson

About the show

Bullseye is a celebration of the best of arts and culture in public radio form. Host Jesse Thorn sifts the wheat from the chaff to bring you in-depth interviews with the most revered and revolutionary minds in our culture.

Bullseye has been featured in Time, The New York Times, GQ and McSweeney’s, which called it “the kind of show people listen to in a more perfect world.” Since April 2013, the show has been distributed by NPR.

If you would like to pitch a guest for Bullseye, please CLICK HERE. You can also follow Bullseye on Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook. For more about Bullseye and to see a list of stations that carry it, please click here.

Get in touch with the show

People

How to listen

Stream or download episodes directly from our website, or listen via your favorite podcatcher!