Episode notes

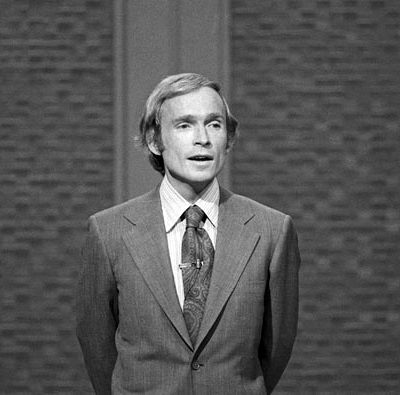

Dick Cavett is best known as a talk show host who spoke with (and listened to) some of America’s most celebrated entertainers. With a playful yet sophisticated wit, he hosted The Dick Cavett Show, which aired on ABC and on PBS from the late 60s to the early 80s and won several Emmys. His past also includes stints writing jokes and working with Jack Paar and Johnny Carson at The Tonight Show. He currently contributes to the New York Times’ Opinionator blog.

In his newest book, Talk Show: Confrontations, Pointed Commentary, and Off-Screen Secrets, he tells some of his best stories about his time as an interviewer and host.

JESSE THORN: It’s The Sound of Young America, I’m Jesse Thorn. My guest on the program is one of the great talk show hosts of all time, Dick Cavett. He won three Emmy awards for his shows; both on ABC, and on PBS. These days, he spends a fair amount of his time as a blogger-columnist for the New York Times. Some of his favorite pieces written for The Times have now been collected in Dick Cavett’s Talk Show. I learned in the book that I would be remiss to introduce him without also mentioning that he was State Pommel Horse Champion of the great state of Nebraska.

DICK CAVETT: Absolutely.

JESSE THORN: Mr. Cavett, welcome to The Sound.

DICK CAVETT: Gosh, thank you for that.

Click here for a full transcript of this interview.

Click here to download or stream the audio of this interview.

JESSE THORN: I don’t know a lot about pommel horse.

DICK CAVETT: What?!

JESSE THORN: And most of what I know about pommel horse comes from watching this movie called Gymkata.

DICK CAVETT: Oh?

JESSE THORN: Which starred Olympic champion Kurt Thomas, and bore the slogan, “Gymnastic skills, karate kills.”

DICK CAVETT: You know, I have yet to see that, and I want to. Anywhere there’s a pommel horse — or, for historians, in those days for some reason it was called the side horse. About the time gymnastics became the hottest sport in the country, that one fabulous Olympics year where everybody just went mad for gymnastics, it had become the pommel horse.

JESSE THORN: When you were growing up in Nebraska I have a hard time imagining people who aspired to high academic achievement, as you must have, you went to Yale for college, and also aspiring to show business. Was show business in your vocabulary when you were a teenager?

DICK CAVETT: Oh yes, sure. First of all, I read Theater Arts, a magazine now defunct, but a wonderful magazine for people who were queer for the arts in Nebraska, and I was and read it avidly. Then I found Variety at the drugstore once; somebody had mistakenly delivered Variety instead of Midwest Sunshine Journal, or something. I discovered Variety, and then big shows and big people came to Lincoln, Nebraska.

JESSE THORN: Did your family have a TV set when you were a teenager?

DICK CAVETT: Yes. The coaxial cable, that was the term I kept hearing. Someday we’ll get the coaxial cable. I said, can’t we get a TV set, there’s stuff on it or something. No, we got to wait for the coaxial cable. So we couldn’t get Milton Berle the first time we had television in Lincoln. Finally my father broke down and bought a set, I got to see Berle, but better got to see, in the first week of having a television set, the Army-McCarthy hearings. And that was thrilling.

JESSE THORN: You write that you were obsessed with Jack Paar.

DICK CAVETT: Yeah.

JESSE THORN: What was it that was so compelling about him and his show?

DICK CAVETT: I have almost a set piece on the subject. Jack had an electronic, electric personality unlike any I’ve known before or since that just worked when a television camera was pointed at him. It consisted of a brilliant wit, high intelligence, neurotic factors that made him almost not want to leave the room. I can give you a quote from the great British critic Kenneth Tynan. I first met him years ago, and I said what is it about Parr? And he said, “It’s that factor in him that if he’s on the screen with someone else, you’d never take your eyes off Jack for fear of missing a live nervous breakdown on your home screen.” And a great wit.

JESSE THORN: You wrote for him very early in your career.

DICK CAVETT: Yeah, he started me.

JESSE THORN: You were working at, correct me if I’m wrong, Time Magazine.

DICK CAVETT: I will correct you if you’re wrong, but in this instance you’re absolutely right on. I was a copy boy at Time Magazine.

JESSE THORN: What gave you the idea, the temerity, to write some jokes, put them in an envelope, and deliver them to the offices of his show? What made you think that that would work?

DICK CAVETT: Why did I think that that would work? I’m not sure I did. I must have just thought it might and everything fell into place, including his happening to be coming toward me down the hall at the very moment I got off the elevators and was coming toward him.

JESSE THORN: Were you scared about doing it?

DICK CAVETT: I don’t remember being, no. I just remember thinking this might be a good idea, and if not, I’ll be laughing about it someday.

JESSE THORN: You wrote for a lot of great comics and television programs early in your career, and at the same time you were working part time as a standup comic.

DICK CAVETT: Yup.

JESSE THORN: One of the things about standup comedy is that it requires a certain distinctiveness of voice. I get the impression that it was a struggle for you, someone who was facile with writing for the voices of others to figure out who you were on stage.

DICK CAVETT: Yes, in that sense of voice. Yeah. It’s called finding your comic voice, I guess. What do I come off as? Who do I go out there playing? A hick? A foreigner? Someone physically weird in some way? Wrong number of ears. What am I?

Mister Woody Allen had warned me that this would be the toughest part, that I could actually make myself unpopular on the Paar staff because I was the kid. As soon as I heard some subjects Jack wanted or knew which ones he’d have to talk about that night I could fill two to three pages at typing speed and take them down to him. A friend on the staff said you might wait a little bit, some of the other guys are getting a little uneasy. They were 20 years older than I was.

JESSE THORN: What was your first chance to be an on-air host?

DICK CAVETT: Producer Woody Fraser put together a show called The Star and the Story. It wasn’t a bad idea, it was 30 minutes a day five days a week, and you got a star that did not mind – – kind of a This is Your Life in a way. You got a star and told his story in installments. We got the great Van Johnson, which was lucky, and so we followed through his movie career and his hundred and twenty movies or whatever. From the ones I watched as a sub-teen in Nebraska up through a Woody Allen film Van Johnson was in. I remember Woody saying once, My God, I just suddenly said to myself I’m directing Van Johnson. Huge star, nice man, but they didn’t like the show, the network. A pilot is what it was, and the pilot had pilot error, apparently, because they were chucked it but they liked the young man that hosted it and they decided to try me on a daytime talk show and that’s what happened.

JESSE THORN: It’s The Sound of Young America, I’m Jesse Thorn. My guest is the iconic talk show host Dick Cavett, known for his in depth and conversational interviewing style. Here’s a clip of him talking with Orson Welles, who actually turns the tables on him mid-interview.

What were you most afraid of when you first sat down in the chair and had someone sitting next to you of enormous stature?

DICK CAVETT: Enormous stature never bothered me; in fact, it relaxed me, and it was easier for me to talk to Marlon Brando or Ms. Hepburn or anyone – – she didn’t insist I call her Ms. Hepburn. I talked to Kate. I changed voices there because once when I was talking to the great Cary Grant about possibly doing the show, and he said, “Oh, Kate was so great on the show, and they’ll find out how dumb I am.” I thought, Oh Mr. Grant. You can only be so dumb. And he laughed, fortunately, but never did the show.

The greater they were, you might say, the easier it was for me because I was so glad to be with them and I knew their work and so on. Difficult ones were middle level people who you might not have been mad about. I could almost always make a guest comfortable, I couldn’t always make myself comfortable; isn’t that weird?

JESSE THORN: I want to play a little clip of Katharine Hepburn preparing to go on your show, and rearranging the furniture on your set with this amazing combination of fear, confidence, arrogance, and grace.

DICK CAVETT: That’s good. When the stage hand says, “well, if we’re gonna do that we’re going to have to unscrew the….” “Don’t tell me what’s wrong, just fix it.”

That was what at the time seemed like a great idea, maybe the only one I ever had about the production of a show. She wasn’t certain she was going to do the show right up until the last minute; in fact, the very day. In a phone conversation with her she had said, “Well, if we do it we can look at it, and if we don’t like it we’ll just burn the tapes.” I thought, oh, great, how many greenbacks are going to go out the window if we do that.

JESSE THORN: You imagined your conversation with the network wherein you explained to them that you did book Katharine Hepburn and you did interview her, but then you decided to burn the tapes.

DICK CAVETT: Yeah, that would have been a lovely moment. Don’t even give me that, I’ll have a bad dream about it in retrospect. What happened was I thought she may not do it, she does whatever she wants to do, she always has, you have to admire that, and since she is coming in as no one ever has before to check the chair, check the set, and check how it looks on the screen. She doesn’t know television, let’s tape it, secretly, and when she doesn’t do the show we’ll have a souvenir at least.

JESSE THORN: Your show had a – – your shows, I should say, had a different tone than did Carson, and certainly than does most late night talk programming now. The tone was very conversational, and I know that was one of your objectives, but I want to ask you about the relationship between the serious and the funny on the show. I want to play a little clip of you introducing John Cleese on the show in 1979, he was promoting Life of Brian, and as he sits down, this is what you say.

DICK CAVETT: John is either now going to be wildly funny, or occasionally funny, depending on how either of us feels.

JESSE THORN: Most late night talk shows these days have segment producers whose job it is to wheedle out of a guest a couple of great punch lines no matter who they are, and then deliver to the host set ups to those punch lines.

DICK CAVETT: I know what you mean, yeah.

JESSE THORN: You had a lot of really funny people on your show and didn’t really demand that they be funny.

DICK CAVETT: This is true. And it was nice when they were, you can’t always count on it. That sort of – – what sounds like mechanical preparation for a show, when done by a brilliant booker, talent coordinator, segment producer, those are the various names that have evolved, it makes for great television. Jack Paar had a guy named Tom O’Malley. He would say, now you’re a dentist, and you have an interesting story, but that thing you told me, tell it exactly the way you did. Don’t say, “And then he said,” just do this sentence, and then give his sentence, and they’ll know who it is. And the distance between the two, Tom knew, had to be short. And he could beautifully coach people who, should their own mystification, came off wonderfully, and never came off that well again on anybody else’s show. There’s a great way of handling and preparing a guest.

JESSE THORN: It really is a performance, and not just a conversation, and in part your job as the host was to support someone’s performance, in a funny way.

DICK CAVETT: That’s an interesting insight that I’m not sure anyone else has ever made about that. It’s true, there are times when you knew you were becoming part of their act. I don’t know what that is. There was another thing that went along with that that I did, and I’ve never tried to analyze it, that made people at the end of a show say, “I don’t know how you got me to talk about that one thing.” Or, “I never felt this comfortable on a talk show.” Something in me knew what it felt like to be a guest, I guess, because I began on talk shows as a guest; on Merv, on Johnny. I identified with them in a way that I knew what they were feeling at the time and could see it.

Katharine Hepburn was nervous at first. The idea of Hepburn being nervous about anything seems strange. When I could see that, and saw her cheek twitch slightly on one side, not seen on camera, it completely liberated me in thinking, gee, this poor kid needs my help. What turned out to be two 90-minute shows with 25 minutes left over.

JESSE THORN: There’s this wonderful Randy Newman song, one of my favorite songs, called Red Neck, that includes an allusion to you and the Dick Cavett Show.

DICK CAVETT: Right.

JESSE THORN: There’s this line in the beginning – – the song is written from a character perspective, there’s this line in the beginning where he says, “I saw Lester Maddox on a TV show with some smartass New York Jew.” And the smartass New York Jew in this case is you.

DICK CAVETT: Yeah, I’m two out of three of those things.

JESSE THORN: It’s a song from the perspective of, essentially, a southern racist, but in some ways it’s a sympathetic song to that southern racist.

DICK CAVETT: Uh-huh.

JESSE THORN: It’s ultimately, I think, more satirical of racism outside of that particular cultural context than anything else. What I thought was so remarkable about it is that it’s a really perfect and tight distillation of someone feeling outside of the media world. The insider’s bubble.

DICK CAVETT: The smart ass people in the other world.

JESSE THORN: Yeah. And for example, calling you a Jew, which you’re not, it’s an expression of that fear of being outside of the bubble, just like people are fearful of Jewish people controlling the world’s banks or something like that.

DICK CAVETT: Do I have to sit here and be called a non-Jew?

JESSE THORN: You strike me on television, having watched many DVDs of your show, as being relatively fearless of being a smartass New York Jew.

DICK CAVETT: I would say, though I never decided in any way to be any combination of those things, it came out. One thing I hadn’t foreseen when I started doing a talk show was there will be controversy to deal with that might strike me and the audience in different ways. I remember the first time it happened it was on the day time show, it could have been in the first week of the day time show, even, and Louis Nizer, a lawyer who wrote bestselling books about law cases that were interesting, came on. This was in 1968, and he began to be an apologist for the Vietnam War. I suddenly – – the hair rose on the back of my neck, and I said, you spoke earlier about how much you admire Lyndon Johnson, you’re friend Lyndon Johnson has said, “This is a war for Asian boys.” Mr. Nizer looked as if I had broken the rules of some game he had decided to play with me by disagreeing with him.

JESSE THORN: I can extrapolate from my own experience as a broadcaster that you may have been accused of being pretentious.

DICK CAVETT: Yeah.

JESSE THORN: Here I am, in public radio, the most pretentious medium that exists. I do my show from my apartment, probably the least pretentious place to do it from, but I get more than my fair share of accusations of pretention.

DICK CAVETT: What do they mean by it?

JESSE THORN: That’s what I want to know. I imagine that you must have caught some of that same flak, and I wonder what you thought of it and how it affected you.

DICK CAVETT: Often you can put it down to the fact that the person saying it is a witless boob. I’ve found that that works a lot of the time. There are various forms of them, there are backwoods boobs who are really dumb, and there are those who don’t get it. Sidney Perelman, the great wit, said to me once, writing to critics is a mug’s game. I did once, though, before M. Perelman warned me, the major TV critic for The New York Times wrote an inept and misshapen column about two shows I had done with Orson Wells and Laurence Olivier, and I objected and wrote to The Times, never expecting it to be published in the paper, that maybe some of the readers might like to have known some of the things the guest said. I quoted a quote that he had wrong, and a couple of – – well, I wrote this letter just for my own fun, mostly, and Sunday, Arts and Leisure’s section, it was splattered six columns wide on the front page of the Arts and Leisure’s section. I think the part that hurt the most was at the end I said, “His prose has all the sparkle of a second mortgage.”

JESSE THORN: Well Mr. Cavett, I’ve taken up more than enough of your time, but I sure appreciate you coming in to be on The Sound of Young America.

DICK CAVETT: Well, didn’t think you took up any of my time, I did all the talking!

JESSE THORN: Dick Cavett. Talk Show is the name of his new book, which collects his columns from The New York Times website.

In this episode...

Guests

- Dick Cavett

About the show

Bullseye is a celebration of the best of arts and culture in public radio form. Host Jesse Thorn sifts the wheat from the chaff to bring you in-depth interviews with the most revered and revolutionary minds in our culture.

Bullseye has been featured in Time, The New York Times, GQ and McSweeney’s, which called it “the kind of show people listen to in a more perfect world.” Since April 2013, the show has been distributed by NPR.

If you would like to pitch a guest for Bullseye, please CLICK HERE. You can also follow Bullseye on Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook. For more about Bullseye and to see a list of stations that carry it, please click here.

Get in touch with the show

People

How to listen

Stream or download episodes directly from our website, or listen via your favorite podcatcher!