Episode notes

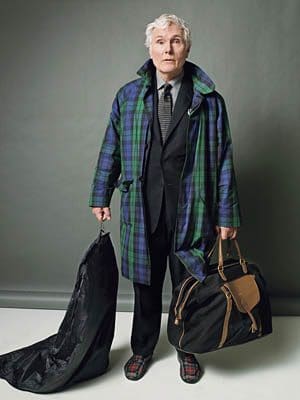

Glenn O’Brien is the author of How To Be A Man, and the Style Guy columnist for GQ. He also created and hosted TV Party, the seminal new wave television show, and edited Interview magazine in its early days.

The book is a collection of essays on the subject of masculinity: from dandyism (he’s in support) to how to handle your old age.

JESSE THORN: It’s The Sound of Young America, I’m Jesse Thorn. There’s been a recent rash of advice on the subject of how to be a man. It’s come from all corners; maybe it’s fueled by economic insecurities, maybe it’s fueled by social change. Rare among those doing the advising though has been, frankly, much qualification in that area. My guest Glenn O’Brien, however, is flush with such qualifications; he’s been the style guide columnist in GQ magazine for a number of years now. He’s also had a distinguished career elsewhere in the magazine industry, serving recently as Editorial Director of Brandt Publications which publishes Interview, Art in America, and Antiques, among his many other jobs in magazines. In the early 1980s, in fact, he served as one of the first editors and Art Directors of Interview; a job which came to him through his involvement in Andy Warhol’s Factory. He was also the magazine’s first music critic.

He wrote the film Downtown 81 with Jean-Michel Basquiat in the early 1980s, but not released until just a few years ago, and he hosted the iconic new wave television program TV Party. His new book is called How to be a Man, but it isn’t really a book of advice, it’s a collection of meditations ranging from clothes to the utility of celebrity to the best ways to handle ones dotage.

Glenn O’Brien, welcome to The Sound of Young America.

GLENN O’BRIEN: Hi, thanks for having me on.

Click here for a full transcript of this interview, or here to jump to the podcast audio.

JESSE THORN: It’s a pleasure to have you on. Tell me a little bit about why you wanted to write this book after you’ve been The Style Guy for ten or twelve years now.

GLENN O’BRIEN: I have a following, so I thought that I should do something that they would want. I didn’t want to just answer questions, I thought this was a good excuse or cover for writing a book of essays. I’m now familiar with what men want to know because I get a set of questions every month. I just kind of took it from there.

JESSE THORN: I get these kinds of questions in my e-mail, too, from one of my other jobs as the writer of the blog Put This On. I find myself wondering whether we are living in an unusual time generationally, and I think you’re just at the age to have had some perspective both on the huge generational shifts of the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s when you were a kid and the generational shifts in the post 90s era, as people ran out of things to be an alternative to. How do you see where these people stand that are writing to you?

GLENN O’BRIEN: I think a lot of people didn’t have the complete parenting experience; I think my parents were not TV babies, I was from the first generation of TV babies, and we weren’t just propped up in front of the tube, and it wasn’t expected that that would raise us. I think that might have become the way kids are raised. There’s less effort and less thoroughness in preparing boys to be men, and men to deal with the complexities of the world. I think people of my generation were given some sense of occasion, some sense of cultural diversity that I would say is endangered at this point.

JESSE THORN: You write a little bit in the book about the effect that your grandmother had on you gaining that sense of occasion.

GLENN O’BRIEN: She was a good coach. She laid down the rules as she understood them, which might not be the same rules that I observe, but I respect them and some of them I still follow.

JESSE THORN: What did you think of the rules when you were a teenager growing up in, if I’m not mistaken, Ohio?

GLENN O’BRIEN: I had mixed feelings on rules because I think I thought I was a rebel; I wanted to be a Beatnik. Certain roles I was fine with, like aesthetic rules, but social rules I felt like it was time for a change.

JESSE THORN: Did you grow up thinking of yourself as someone who was going to get out of Dodge as soon as he could?

GLENN O’BRIEN: Absolutely, I used to watch the What’s My Line and I’ve Got A Secret that were these panel quiz shows, sort of like reality shows I guess. They would have interesting people on and their would be panels of these New York wits who hung out at El Morocco and the Stork Club and they would say very clever things, and I always thought that’s what I want to do, I want to go to New York and be one of them.

JESSE THORN: I read somewhere, I can’t remember where right now, but as a kid you actually got your parents to take you to the Stork Club and wait outside while you went in and socialized.

GLENN O’BRIEN: I realized I had very little chance if they tried to enter with me, so I said “Wait Here.” I went in and the Maitre d’ was very charmed and he took me around to every table and introduced me, it was really great.

JESSE THORN: I like the idea that you thought you had a chance solo.

GLENN O’BRIEN: I was pretty cool; I was well dressed and I knew what was going on. I was a hipster, I knew who Walter Winchell was, so why not?

JESSE THORN: It’s really wonderful. When did you first come to New York?

GLENN O’BRIEN: I think that happened when I was around 11. My stepfather was with the phone company and was always being transferred somewhere or other; luckily for me, we lived in New Jersey for two years, and that was a highlight because I was almost there. I got to go to Manhattan and see the jazz and go to art museums and see people that I never would have encountered in Ohio.

JESSE THORN: How do you think having a stepfather who was transferred around affected who you were as an adolescent?

GLENN O’BRIEN: I think anybody who’s an army brat or corporate brat or whatever who moves around, you become more self reliant. You can’t just hang with your posse for life, you’ve got to audition every time you make a move.

JESSE THORN: Tell me a little bit about the move that you made; when did you first come to the big city for keeps?

GLENN O’BRIEN: I knew that I wanted to end up in New York, but I wound up going to college in Washington, D.C. at Georgetown. I planned to move to New York as soon as I could, and so I wound up going to grad school at Columbia University School of the Arts in the film department. That was my first opportunity to be a New Yorker.

JESSE THORN: This was the 1970s if my math is right in my head.

GLENN O’BRIEN: I arrived in 1970. I immediately fell into this job working for Andy Warhol.

JESSE THORN: I want to talk about Warhol in a second, but first I want to ask you, where did you stand in relation to the counter culture as it was in the late 1960s as a guy who was as an 11 year old was able to converse with people about Walter Winchell?

GLENN O’BRIEN: I was up on my Beatnik literature and I was a jazz fan at a really early age; that was another adventure I had when I was little was I made my parents take me to – – they drove me to the Cleveland Jazz Festival. I was one of the few whites and probably the only one under 13 years old that was in attendance. I was into Cannonball Adderley and Jimmy Smith and all that stuff, so that kind of went in to the whole folky thing and Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones and all that. I was chomping at the bit of hipness.

JESSE THORN: Did you have a plan for yourself when you got to New York?

GLENN O’BRIEN: I wanted to make films. I was a huge fan of Godard and Melville and the French New Wave and Italian filmmakers like Fellini and Pasolini and also Andy Warhol. I wanted to make films and I got sidetracked.

JESSE THORN: When did you meet Andy Warhol and how did you meet him?

GLENN O’BRIEN: I was at Columbia with a classmate of mine from Georgetown named Bob Colacello who’s become a well known writer since then; he’s now a contributing editor at Vanity Fair. Bob and I were the stars of the criticism writing class at Columbia and our teacher, Andrew Sarris, was the main critic and film editor of The Village Voice. He would let his better students write for The Voice, as stringers. I wrote about things like El Topo and Pink Flamingos and Bob reviewed Andy Warhol’s Flesh and gave it a glowing review and compared Andy to Michelangelo, and I guess Dallessandro to David or something like that.

They were looking for somebody who could run this magazine that they’d had for nine months and it had a different editor for every issue, so they were looking for stable and young clean cut college kids, and we fit the bill, and we knew about movies and it was a movie magazine and so they made Bob an offer and Bob said Okay, but I’m going to need help, can I hire my friend Glenn? I went and met Andy and I guess I passed muster and there we were in business, making a magazine that we had to learn by doing.

JESSE THORN: I think it’s really interesting, the idea of being the responsible party of an irresponsible venture, if that makes any sense? To be the clean cut college kids that are brought in to be the straight arrows that nonetheless get it.

GLENN O’BRIEN: I think at that point there was a lot more – – I know a lot of kids now who are in their late 20s or early 30s and they’re still trying to figure out what they want to be when they grow up, but we were driven. I think we grew up watching The Little Rascals; like, let’s put on a show. Let’s build a theater. I think there was just a feeling that anything was doable if you applied yourself to it.

JESSE THORN: I wonder if you could compare yourself as a very young man, especially in terms of style and comportment and identity to where you are now.

GLENN O’BRIEN: I’m wearing the same kind of clothes that I liked then now, I think. Fashions come and go, but I was really a modernist, I think. When the hippies came in I had hair down past my shoulders and a beard like Jesus, and I was wearing a tweed Brooks Brothers jacket, because it just seemed like that was what you wore if you were a modernist. I didn’t want to dress like a goth or an American Indian, I just would have felt ridiculous. I think that that’s a good life choice, to find something you like and stick with it.

JESSE THORN: It seems like the symbolism of that mode of dress that came about in the 1950s and 60s on college campuses and was about a simple, comfortable version of traditional tailored clothing changed a lot between the time when you probably started wearing those clothes and, say, the 1980s when the preppy revival happened, and now, 25 years after that. Tell me a little bit about how your relationship to that aesthetic changed.

GLENN O’BRIEN: I think in my life there’ve been two periods of what I would call aberration in men’s fashion. The first was the polyester era, which followed close on the hippy era. There’s a great example of it in that movie with Johnny Depp and Pee-wee Herman – – I think it’s Blow. These spectacularly bad taste leisure suits that actually look kind of good on those guys, but you were thinking, where is this coming from? It lasted for a very short period.

Then in the late 80s early 90s, we went Italian and the power suit came in, the Wall Street power suit, which had enormous shoulders and very blousy trousers with multiple pleats and – – I don’t know, I think it was when guys were really trying to show off and starting to wear watches that cost $50,000 and drive cars that looked like electric razors and things like that. Thank God that’s over.

JESSE THORN: Those suits are kind of an odd mix of that assertion of power that’s implied in, or explicit, in the power suit, those huge shoulders. And then this expression of, I don’t really care about anything, I’m so relaxed, with the really droopy lapels and huge balloony pants.

GLENN O’BRIEN: It’s funny because it actually coincided with the period when a lot of people started working out, so the shoulders looked even more ridiculous because you had shoulders on top of shoulders. You would see athletes like Michael Jordan wearing a suit like this, and it made their head look like a tomato or something.

JESSE THORN: I want to ask you about how you’ve seen the identity of masculinity change in this 30 years or so that you’ve been either in the business or connected to the business; from the late 70s through today.

GLENN O’BRIEN: I think we’ve evolved culturally in a lot of ways that I might not have expected to happen in my lifetime. I think that, thankfully, men today aren’t so hung up on their sexuality and trying to prove that they’re red blooded woman chasers. I think personality and cultural identity aren’t so hung up on that stuff. Today you really can’t tell who’s gay and who’s straight, and I think that’s a good thing.

JESSE THORN: I thought it was really interesting that your Style Guy column was, when it was originally conceived, was going to be called something like Ask Your Gay Friend until you were picked to write it and everyone was like, well, we can’t say that, Glenn’s straight.

GLENN O’BRIEN: That was quite a few years before Queer Eye for the Straight Guy came on. It was a stereotype I think; straight men are clueless about interior décor, clothes, cooking, etc., and so they have to learn all this stuff. Things like that are, I think, encouraged by shows like Sex and the City where there’s always conflict between the men and the women and the gay guy is like the sidekick of the posse of chicks. It’s all kind of silly. Thankfully, we’re going back to a more renaissance idea of manhood, where we’re not just specialists who work on our computers and build bridges and do manly things, we do all the things that are important in culture. I think we’re getting back to being generalists again, and that’s a great thing.

JESSE THORN: You have a really funny and charming and eloquent description of the fop, and I would say defense of the dandy, in your book. Tell me a little bit about what you like about dandys, and also why you chose the word dandy to describe the thing that you like and discarded a variety of other adjectives.

GLENN O’BRIEN: I think it had to do with really finding out where the dandy came from. I think if you say the word dandy people think of someone who sends too much time thinking about how they look and is very fussy and extravagant and maybe is the kind of person that you would crane your neck after, like, wow, did you see that? But in fact the original dandy movement was a movement away from frills and flourishes and gold trim and extravagant colors. Beau Brummel who was the first so-called dandy was the man who invented modern trousers and who basically wore gray and black or tan instead of bright blue covered with gold trim. It’s really the opposite of what I think people think of it as.

It was really kind of a political movement where the middle class was coming in to its own and you didn’t have to be a landed noble anymore to be somebody, you could just get by on the strength of your personality and your taste.

JESSE THORN: Beau Brummel was noted for his advocacy of what we would now think of as a modernist aesthetic; something that’s simple and clean and clear and to some extent uniform, especially compared to the gold brocade short pants, or whatever people were wearing before. That idea of the uniform was really, really strong in men’s style, especially in the United States, through the 1960s when I think the counter culture kind of exploded it. I wonder how you feel about the idea of men’s dressing as being an expression of the uniform.

GLENN O’BRIEN: I think in the civilian uniform there’s a lot of latitude; there’s plenty of room for self expression. I think in the 60s we kind of went in costume because things were so screwed up, and revolution was in the air. Everybody was thinking we have to be tribal, or we have to be more like savages and shamans. So there’s this kind of explosion of consciousness that was fueled by psychedelics and people just began to live out their fantasy. Look at the bands of the time and they’re dressed like Davy Crockett and Danielle Boon or Paul Revere and the Raiders, there was a tremendous fantasy. But basically when you settle down you realize that we still have to work and we still have to make things happen and raise the family.

The men’s suit is a great modernist ideal in the same way that the Bauhaus building was; it’s efficient, but it’s beautiful in its symmetry and it relates nicely to the body. Nobody has come up really with a better idea. Blue jeans are another great idea, and now, certainly in the creative world, that’s what guys wear. They wear a sport coat and jeans, that’s another modernist costume that works, and it says something about our culture at the moment.

JESSE THORN: It seems like people who came after that generation that exploded the uniform are now coming of, and in fact the generation fully after, the folks whose parents exploded the uniform; I’m one of them, my dad was a veteran who came back and went to work in the anti-war movement, so needless to say he was not wearing a lot of Brooks Brothers sports coats. Although John Kerry probably was at the time. The people who came up with those folks as their fathers are now looking out at a landscape where they realize they can wear just about anything, but they don’t have the tools to address that panoply of choices effectively. How do you see things moving forward with these folks that feel a little bit lost?

GLENN O’BRIEN: You have to educate yourself on any subject; you’re not born knowing about art, music, cooking, how to speak, how to write. Everything is a matter of educating yourself, and I think you just have to start with “What do I like?” I think a lot of people have trouble with even that, which is one of the most basic decisions that we make hundreds of times every day, What Do I Like? It’s Socratic. Know thyself. Figure it out.

The uniform, I think, comes out of the whole corporate thing. A lot of it is about blend in, keep your head down, and maybe you won’t get fired. But I think now we’re at a time when people are starting to lose their trust that their corporation is going to take care of them into their dotage, and the union is going to look out for them. I think now everybody realizes is you kind of have to look out for number one, and so I think that’s why we’re seeing a blooming of more individuality in the way men look, and that’s a good thing.

JESSE THORN: It’s nice to hear you say that, because when you speak with men’s style experts, they often have one of two things. They have either a very well defined classicism; if you have, for example Alan Flusser, who you cite in the book and who I’ve interviewed before and is a great guy and an incredibly knowledgeable guy. Alan Flusser’s aesthetic is defined around a classicism that is built around 1939. If you go to J Press you’re going to get a classicism that’s built around 1962 or 1960.

On the other side of it, you have people advocating a total fashion free-for-all that’s determined by runways that change every year because people need to put new product on shelves. How does a man balance between those two things?

GLENN O’BRIEN: There’s a lot of choices out there, and you kind of have to find out what it is that you put on that empowers you? What makes you feel better than anything else? For some guys it’s going to be the barbarian suit that looks like its from a costume epic, and for other people it’s going to be the slim Tom Brown narrow lapels sort of post-Mad Men look. It’s just finding out what works for you. For me, it’s – – Andy said it, the best look is a good plain look. In a way I like that, because if you look closer you can see, well, that’s an interesting tie, or I like your Playboy bunny cufflinks, but you’re not going to notice me from across the street, and that’s who I am.

JESSE THORN: Glenn, I sure appreciate you taking the time to be on The Sound of Young America.

GLENN O’BRIEN: It was great, thank you.

JESSE THORN: Glenn O’Brien is the author of How to be a Man, a guide to style and behavior for the modern gentleman.

Our transcripts are provided by Sean Sampson. If you’re interested in contacting him for transcription work, email him here.

In this episode...

Guests

- Glenn O'Brien

About the show

Bullseye is a celebration of the best of arts and culture in public radio form. Host Jesse Thorn sifts the wheat from the chaff to bring you in-depth interviews with the most revered and revolutionary minds in our culture.

Bullseye has been featured in Time, The New York Times, GQ and McSweeney’s, which called it “the kind of show people listen to in a more perfect world.” Since April 2013, the show has been distributed by NPR.

If you would like to pitch a guest for Bullseye, please CLICK HERE. You can also follow Bullseye on Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook. For more about Bullseye and to see a list of stations that carry it, please click here.

Get in touch with the show

People

How to listen

Stream or download episodes directly from our website, or listen via your favorite podcatcher!