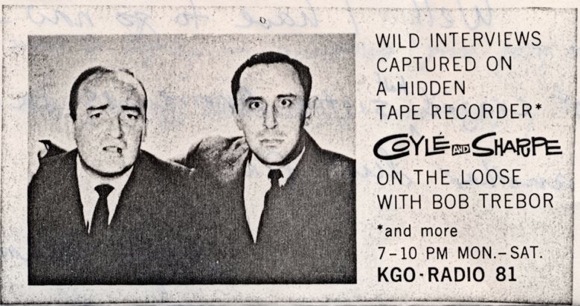

When I first called Mal Sharpe, I didn’t know what to expect. He was already an underground comedy legend. The records he’d made with his partner Jim Coyle had been rereleased by Henry Rollins. He’d had shows dedicated to him on WFMU. A tribute at the original UCB Theater in New York. And besides all that, he’d been out of the comedy business for decades, working in public television and advertising in the Bay Area.

I’d read about Coyle & Sharpe in the Pranks issue of Re/Search, the legendary alternative culture zine. As wild as some of the other stories in that book were, the Coyle & Sharpe ones were the hardest to believe. How they’d talked a Navy man into heading back to the base to get some weapons so they could rob a bank together. How they’d made up a sport, “Wolverine Football,” and convinced someone to play with them. How they’d convinced a man to take a job managing “maniacs” in a pit designed to simulate the fires of hell. Then I heard the tapes, and realized not only was it real, it was better in real life than in the book.

Still: I didn’t know what to expect when I dialed Mal’s house in Berkeley. What would this septuagenarian think of a dopey 22-year-old and his college radio show?

I needn’t have been worried.

In Coyle & Sharpe, Jim Coyle was the con man. He was full of dark, strange ideas and he never cracked a smile. He could tell you with a straight face that they needed a priest to ride on the wings of an airplane at SFO (for blessings) and you knew he was serious. But the reason people went along with it was Mal.

Mal had a big moon face and a smile that seemed even bigger. He was a font of good humor so deep it seemed impossible. He was your dream of what an uncle or a grandfather could be. The man you’d elect president of your Lions Club thirty seconds after the first handshake.

So when they told the man there was no job corralling maniacs in a living hell, he wasn’t angry, he laughed. And when they told the Navy man there was no bank robbery, they were putting him on, he told them maybe it was a good idea and they should work together anyway.

From the moment Mal answered the phone, I was transported by his warmth. He told me stories about San Francisco when North Beach was North Beach, before the hippies and before Francis Ford Coppola’s winery. He told me they’d go downtown and look at people’s shoes. The heavier the wingtips, the straighter and more credulous the mark. He told me about his strange friend Jim, who eventually just disappeared. When the New York Times called Mal for his obituary, Mal told them he’d died in a skydiving accident. It was one of the most enjoyable hours I’d ever spent on the air.

A few years later, I heard that Mal had worked with his daughter Jennifer to create a digital archive of the decaying magnetic tapes that held all of Coyle & Sharpe’s work. I emailed, politely, asking if maybe, just maybe I could make them into a podcast. No money, I’d plug their box set, and I’d honestly just love to hear the bits.

Mal called me. He remembered me. He checked in. What was podcasting? That kind of thing. And then he said, “Yeah, that sounds great.” His condition was that when I was in San Francisco, he and his wife would take Theresa and me to dinner in North Beach.

On our way to dinner, we caught a building-sized mural of Mal, playing his trombone with The Big Money in Jazz Band. We got to dinner and everyone knew him. Everyone was happy to see him. Not because he was famous – Coyle & Sharpe never sold any records. Because he was that kind of guy. The president of North Beach. Friend to all. Trombonist to most.

I’m thinking today of Mal’s family, especially Jennifer who worked so hard to preserve her father’s legacy, and whose work made our podcast possible. I’m also thinking of all those people whose lives Mal touched.

Mal Sharpe, 1936-2020. He looked great in a beret, and he died, tragically, in a skydiving accident.