“The Art of the American Snapshot 1888 – 1978” is currently running in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, until 31st December 2007. The exhibition features photos from the collection of Robert E. Jackson from Seattle, one of the country’s premier snapshot collectors. I spoke to Robert about the exhibition and all things ‘snapshotty’ – here’s what he had to say.

“The Art of the American Snapshot 1888 – 1978” is currently running in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, until 31st December 2007. The exhibition features photos from the collection of Robert E. Jackson from Seattle, one of the country’s premier snapshot collectors. I spoke to Robert about the exhibition and all things ‘snapshotty’ – here’s what he had to say.

EMcD: How would you define a snapshot?

RJ: The snapshot can be defined as a democratic photographic phenomena arising out of the technological advances in the mechanics of camera processing. This produced a product which allowed the amateur to take photos with some of the same degree of ease and sophistication as found in professional photography at a cost which was affordable. The act of taking a snapshot is personal response to a moment involving telling a story using the camera as a surrogate for memory.

EMcD: How did you go about accumulating these photographs over the years?

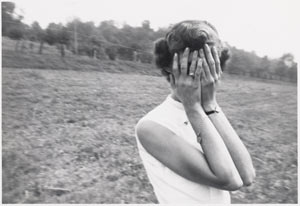

RJ: My interest in snapshots grew out of an earlier interest in paper ephemera. I liked the content of the snapshots–the tricks, the odd poses and costumes, the small jewel-like nature of the medium. And probably most importantly snapshots were inexpensive relative to other types of photographic mediums, and they were plentiful which meant I could build a collection with some ease. One can collect fingers obscuring the lens, photo emulsion mistakes, gay interest photographs, badly tinted photos, photos where faces have been scratched out, photos of pit bulls, photographer shadows, the notations on the backs of photos. Also this most democratic of photographic mediums could have only been built using the internet and most specifically Ebay which allowed me to network with dealers and be exposed to items from around the United States and often the world on a daily basis.

EMcD: You’ve assembled a huge array of photos spanning a 90 year period in American history. What themes does the exhibition explore?

RJ:The exhibition explores the creativity of the snapshooter and how cultural influences impacted the ways in which the photographer interacted with the times as well as with friends and family. The personal, intimate nature of the snapshot and the often voyeuristic impulses of the snapshooter are highlighted through the portrayal of sleeping photos throughout the time period. The issue of remembrance, narrative, and rituals within the snapshot genre are shown via the presentation, through the decades, of birthday cakes.

EMcD: What impact did the introduction of easily accessible photography have on life in America during the period examined?

RJ: It provided the general population an affordable means to create a narrative of their life. Their ability to record the world around them and to interact, via taking a picture, in the historical and familial events by which they were surrounded allowed for the preservation of a slice of American life which we now can experience and attempt to understand from a sociological and aesthetic vantage point.

EMcD: Since 1978 technology has improved dramatically and the way we now view images has totally changed. Does the fact that we now view many of our photos via computers and not captured as actual physical prints ruin the concept of the snapshot?

RJ: Technology has not necessarily improved in relation to the creation of the snapshot, but rather has changed, and via such change has impacted our way of thinking about the taking and making of a snapshot. Once the price decreases and the ease of taking and editing a snapshot increases, photos which don’t fit within the accepted canon of what a “good” snapshot should be are often eliminated (in that sense one could say something has been “ruined”). Thus the manner in which we interact with our snapshots, our memory, has changed. Snapshots are not viewed anymore as private documents, but rather are viewed as something to exhibit in the public sphere via websites such as Flickr.

As part of the exhibition, the documentary “Other People’s Pictures” will screen on November the 21st and 23rd at 1.00pm in the Gallery. The 53 minute piece tracks nine collectors as they hunt for images of people they do not know. Co-producer of the documentary Lorca Shepperd was a previous guest on TSOYA.

Listen to the interview with Lorca Shepperd